All chips off the same bèta block

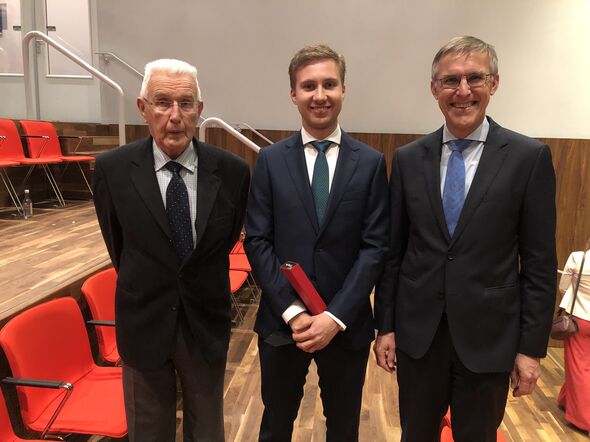

Three generations of physicists

Can you imagine it? Over the kitchen table at home, or at a family party, trying to explain to relatives exactly what it is you are writing about for your final thesis. Arthur Hendriks, who next week officially completes his master's degree at TU/e's Department of Applied Physics, has it much easier than most in this respect. His mom, dad, granddad and brother are all, without exception, chips off the same bèta block; at different times each of them has belonged to this same department, most of them, in fact, to the same group (or its predecessors).

Let's get this family portrait as good as complete right at the outset: Arthur also has two younger sisters, the twins Diana and Suzanne. And they too are studying for a technical degree, Mechanical Engineering - one of them in Eindhoven, the other in Delft. Does this make the latter of the two the black sheep of the family? Mom Doreen laughs. “Well, she certainly doesn't see it that way.”

It was granddad Jan Hendriks, now aged 87, who more than six decades ago got the ball rolling in the field of physics for this family. Born in Rotterdam and raised in Wassenaar and Utrecht, he left home to study Mechanical Engineering at the HTS, the higher vocational education institution of its day. After his four-year course, he started work in 1956 at Philips in Eindhoven. A year later he arrived at TU/e (then still the Technical University (TH) Eindhoven), where he held the position of technical officer at the Department of Mechanical Engineering.

Times were different then, as Arthur learns from his granddad, who is answering a question put by Cursor. The TH had recently opened, as yet few people were on the premises, work relationships were much more formal. “It's commonplace now for students to address their professors by their first name.”

Even though he already had a higher education diploma under his belt, Jan was keen to continue studying, preferably physics. “But Eindhoven wasn't yet offering physics back then,” Arthur explains. So electrical engineering won the day. “I'd heard a professor say that would be the field most similar to physics.”

In 1964, having gained his degree, he started work, joining the scientific staff of the Department of Applied Physics, which had now been founded at the university. At the same time, he was doing research under Professor Zwikker at the Solid State Physics group (which later included Semiconductor Physics, which eventually became the Photonics and Semiconductor Nanophysics group that we have today). “It was there that he gained his doctorate in 1970.”

Now Dr. Hendriks, Jan moved again. This time he had a young family to take with him and they set up home in Den Helder, where he went to work at the Royal Netherlands Naval College (abbreviated in Dutch to KIM) as a senior science lecturer in physics, later adding the study of weapons and ballistics to his remit. Here, too, he pursued research, continuing to do so until his retirement in 1995.

Son Peter, Arthur's dad, recalls how during school vacations he himself could often be found at KIM. How as a teenager he would cycle along the dike to the naval base, would walk in through the back door (“unimaginable today”) and be allowed to play in his father's lab with set-ups involving lasers, optics or electronics. “He would make a sketch and get me to build amplifiers, or a telescope.”

Similarly at school, physics was a subject he sailed through, says Peter. So it was only logical that his next step should be to study further in this field. A decision that brought him to Eindhoven, but not to please his father. “My main motivation was to avoid going to Delft or Enschede.” From 1982 onward, he would spend a good eight years at TU/e.

Peter recalls how small the department was; they had a hundred first-years, but not many more. “We all treated each other in the same easygoing way, felt a strong sense of commitment to each other.” Many of the people whom he met in his first week at TU/e, he still sees on a regular basis, Peter tells us.

It was at the Auletes wind orchestra, part of the Eindhoven Student Music Group (now ESMG Quadrivium) that Peter, by now a third-year student and by his own admission a fanatical clarinet player, met saxophonist and fellow physics student Doreen. It was not love at first sight, she explains. “Only a year later we became a couple.”

Doreen was one of the handful of women students at the physics department at Eindhoven. She had chosen this path having found during her years in high school that she enjoyed all her courses, “even math and physics. I like puzzling things out, and in these subjects this is very obviously what you need to do.” She continues, “My father said, ‘If you do everything equally well and find it all enjoyable, then choose something that will give you good opportunities later on.’ I always enjoyed astronomy too, but I lived in Brabant and at that time I didn't want to go too far from home.”

So physics became her subject, in Eindhoven, where Peter was a year closer to the finish line. He graduated in solid-state physics at the Theoretical Physics group, after which he moved seamlessly into a doctoral study on semiconductor physics, under Professor Wolter. Similarly, Paul Koenraad, now dean of TU/e’s Graduate School and a professor at the Photonics and Semiconductor Nanophysics group, studied for his doctorate under Professor Wolter. “Paul was working on a different subject but, yes, in those days we certainly did spend a great deal of time together.”

When the time came for her own internship, Doreen, now close to graduating in Theoretical Physics, started work under this same Paul. She subsequently took her doctorate under Professor Buschow in Leiden. “But I did my research in Eindhoven, at what was then the NatLab run by Philips. I was working on permanent magnets.”

Doreen and Peter were now sharing an apartment in Eindhoven, and her research plans enabled Doreen to stay in the city. Having gained her doctorate, she started work at Koninklijke Hoogovens, the Dutch steelworks - now Tata Steel - based in IJmuiden. “Initially, I was researching how to make aluminum and steel more malleable; later on, I worked in the department dealing with packaging quality. They were making materials for things like the cans used to hold soft drinks and canned foods.”

Having gained his PhD, Peter was now working for Shell, “first as a researcher in Rijswijk, later offshore in the North Sea. With the addition of two sons, the family was now settled in the Randstad conurbation in the west of the Netherlands. Then in 1999 Shell offered Peter a job in Syria. “At that point we moved the whole family overseas.” Son Mark was four at the time, Arthur eighteen months; their twin sisters Diana and Suzanne were born in Damascus.

It was a time of hopeful change, says Peter succinctly. “The president died and was succeeded by his son - a doctor from London - who is still the president today. Now everything will get better, was the prevailing thought.” And for a while it did, he continues, “but since then times have changed. The country is home to many different beliefs and ethnic groups, and now they are in conflict with one another. Everything that was built up there has gone. It's dreadful.”

In 2003 the family moved to Oman, the scene of Arthur's earliest childhood memories. “I really was very young still, about six years old. I went to an international school, was taught in Dutch, and occasionally in English. There were children from all over the world.” He laughs, “And it was wonderfully warm.”

Back in the Netherlands, the Hendriks family spent a while living in Budel. Doreen meanwhile qualified as a high school teacher and taught physics at a high school in Weert for a couple of years. From here, brothers Arthur and Mark, two years apart in time, made the step into higher education. During their student years, Eindhoven, TU/e and more specifically the Department of Applied Physics would become their second home. As it had for both their parents and their granddad.

I certainly toyed with the idea of doing Mechanical Engineering; everyone in physics seemed to me a bit boring

Arthur laughs. “We did have a choice. Of course we did. But in high school math and physics were my best subjects, and the ones I enjoyed most. Although I certainly toyed with the idea of doing Mechanical Engineering; everyone in physics seemed to me a bit boring.”

Doreen tells how the boys initially stayed at home in Budel and commuted back and forth to uni by train. This changed when Shell came to Peter with a new job offer, this time at Qatar's state-owned oil company. The twin daughters, partway through their fifth year of VWO (the academic stream in high school), moved abroad with their parents; brothers Mark and Arthur stayed behind and moved in together in Eindhoven.

Arthur was now in the second year of his bachelor's degree. “We had WhatsApp and Skype, we could easily stay in touch, and now and again we travelled back and forth. But of course it was a bit strange, especially in the beginning,” he recalls. Doreen adds, laughing, “Without warning they had to do everything for themselves; even just popping home at the weekend with their laundry wasn't an option.”

Peter is still proud of how all four children embraced their new circumstances, he says. How Diana and Suzanne found their feet in Qatar in a strange, new school system and eighteen months later passed their International Baccalaureate. How quickly the two boys became more independent.

Unexpectedly, the whole family is now back in the Netherlands, and has been for a couple of months. Peter and Doreen were supposed to travel on to Kuwait in April for Peter's work, “but then corona came along.” He is now working remotely, awaiting a new visa.

For the time being, mom and dad are living with daughter Diana in the family's apartment in Eindhoven. “She isn't always overjoyed with the arrangement,” says mom Doreen with a wink. In Rotterdam, meanwhile, fifty cubic meters of home contents are waiting in a container, stranded like its owners between Qatar and Kuwait. Arthur, who lives with his brother Mark five minutes' walk away, feels having his parents closer by than usual for a while is “actually quite special”. “Although you get used to it just as quickly.”

Now, at least, they do not have to take a flight to enjoy the moment (next week, Tuesday 13 October) when their youngest son is awarded his master's degree, for his thesis on measuring quantum dots with the aid of cross-sectional scanning tunneling microscopy. Arthur gave his graduation speech on MS Teams, “from the bedroom; can't say it's not strange. But somehow it was good too, not having the pressure of people watching.”

As it happened, he had just finished his experiments when seven months ago corona forced TU/e to (as good as) close its buildings. A case of fortunate timing: “I could get on with my work at home, I had enough information. I carried out some simulations on the computer.”

Arthur is graduating under Paul Koenraad; yes, father Peter's former colleague and mom Doreen's former internship supervisor. But it was a while before all these pieces fell into place. “For the first six months, Paul was unaware that I was Peter's son. I'd not mentioned it. Come what may, I was keen to build my own identity at the university. And at that point I didn't yet know that they had gained their doctorates together. Actually, it only came up at some point when I went on vacation to Qatar; Paul put two and two together.”

Peter, Doreen and Mark will accompany Arthur on Tuesday to his graduation ceremony; his sisters will watch the live stream - as will granddad, at home in Alkmaar. Corona has put paid to any idea of his making the trip to Eindhoven. There will be no festive drink to round off the proceedings, another consequence of the corona restrictions, “but we will probably have lunch together,” says Peter.

In the meantime, Arthur is preparing for the period he will spend as a doctoral candidate at Photonics and Semiconductor Nanophysics, which starts in November. He has been taken on just recently and will be supervised by Professor Andrea Fiore. “The two things I enjoyed most at university were my master's project and my internship in Chicago, for which I also carried out experimental research.”

As he himself says, he is well aware of all the footsteps he is following in, though in itself this has played no role in his career choice. “I'm guided by what I like doing.” His father Peter agrees this is the most important consideration. “Particularly when Mark was deciding, I remember saying, bear in mind that you are choosing to do something that will occupy you for forty, fifty hours a week. It's not the same as doing a course you like in high school for two, three hours a week”.

Arthur actually finds it useful having parents who are well versed in exactly the same material as himself. “Whenever I talk about something in the field of physics, they usually understand it. Especially my dad's eyes light up with recognition, I see that sometimes. What I mostly hear from other students is, ‘no way my parents are going to understand that.’” And, says Arthur, even his granddad keeps a bit of an eye on developments in his former field, and still enjoys reading books on physics, “even if the details are often a bit too specialist.”

That the sisters Diana and Suzanne did not choose physics, but took the exit marked Mechanical Engineering, is not an issue within the Hendriks family. At most it gives cause for a little gentle teasing now and then. Doreen says, “Someone might be on Bol.com looking at a book on quantum mechanics and see an automated suggestion for a book on mechanical engineering - or vice versa. One of us might send a message saying, ‘No way!”

So, there are plenty of brains wired for hard science at the family dinner table, then? “Yes, but science isn't a topic of conversation,” says Peter. “Besides, much of what I do is not very technical.” And over the years Doreen has become somewhat detached from physics, having had her hands full with all the administrative and practical aspects of her husband's overseas career moves. “Although I'll always feel the pull of physics.”

Discussion