What it means to be deaf

‘Learn how to communicate with the deaf and hard of hearing in just a single evening via Dutch Sign Language and take a glimpse into the world of the deaf!’ advertised Studium Generale; the workshop sold out in no time. On a cold, wet Tuesday evening, thirty students made their way to Neuron for the occasion. Cursor was there too.

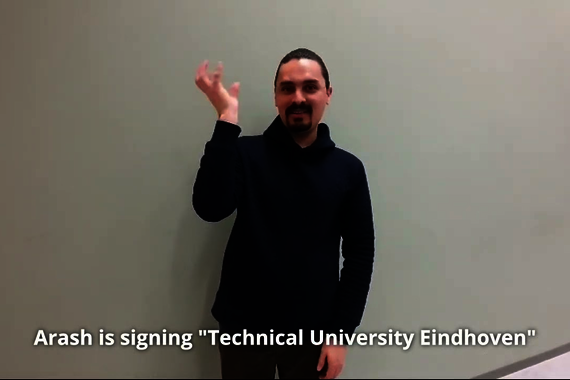

This glimpse into the world of the deaf is offered by expert Arash Ghafari, who was born deaf in Afghanistan and fled to the Netherlands at a young age with his hearing parents and deaf siblings. Here, he learned sign language and studied photography, among other things. He wouldn’t have been able to do this without sign language interpreters.

Interpreters Steffie Hendriks and Jorien Smit have been working for and with Arash for ten years now. Together they form Het Gebarenhuis, available for interactive workshops.

“Interactive” is the right word to describe it. The students feel so comfortable and are so interested that they ask the trio question after question. Are there any benefits to being deaf? Can you hear or feel music and what genre is your favorite? To what extent can AI help turn speech into text? Is it affordable to have an interpreter with you so often?

Arash signs his answers and the interpreters translate for us. Without distracting noises, he can stay focused and sleep well, too. He can feel strong music beats and likes the feeling. AI may be able to help, but still lacks the facial expressions speakers use and those are very important. And fortunately for him, interpreters’ bills are covered.

Grammar

Every country has its own sign language. There are even regional differences within the Netherlands, because some signs are different in Groningen than in Brabant, as Arash has experienced. Interpreter Jorien Smit explains that she doesn’t understand Belgian sign language. Sometimes she interprets for someone who speaks English which means she basically has to translate twice. From English to Dutch in her mind, and then from Dutch to sign language.

Dutch Sign Language (NGT) is not the same thing as Signed Dutch (NmG). They use the former, which has its own grammar. The sentence “Ik ging gisteren naar huis” [I went home yesterday] can be signed with only three signs – those for “yesterday”, “I” and “home”, in that order.

There is also a manual alphabet which Arash has us use. We’re supposed to spell our names for each other in pairs. Some students seem to have quite the hang of it, but they have practiced before. Personally, I’m useless at it.“Learn how to communicate with the deaf in a single evening” has proven to be an overly ambitious promise for me.

Name signs

Anyone who wants to communicate in sign language can come up with their own name sign. Famous people and cities are given a name sign by the community. Arash shows the name signs for Princess Beatrix and Trump (both based on their hairstyles), Max Verstappen (in action) and himself (his bun). Even Minister Dick Schoof has a name sign: a hand making a shoving or pushing motion, a reference to the meaning of his name in Dutch.

Eindhoven is represented by a hand twisting a hanging light bulb, Arnhem by the sign for bridge and Enschede by a hand working with needle and thread (textile city). Tilburg, also a textile city, was given the sign for funfair.

“What’s the sign for beer? Is it possible to sign Houdoe?” the students want to know. None of them know the sign for the Brabantian farewell greeting, but the sign for beer is obvious: a tap being opened.

The initiative for this workshop came from Psychology & Technology student Lente Brinksma, who works as a student assistant at Studium Generale. “I wondered whether it’s possible to study with a hearing impairment,” she says. “What problems would you run into? My grandmother is nearly deaf and wears a cochlear implant.” We just learned that this device is far from perfect; the wearer hears sounds very differently than those around them do. “I’d attended a sign language workshop during a family weekend once and suggested it for the SG program.” This evening, she learned that there is only one university for deaf people in the entire world: Gallaudet in Washington D.C. Neither SG nor Het Gebarenhuis is aware of any deaf students currently enrolled at TU/e.

Most students attended the workshop out of interest, not because they know any deaf or hard-of-hearing students. Charlotte Bronwasser is one of the attendees. She has put her Industrial Design studies on hold until February and is now looking for research topics. Perhaps sign language combined with technology could be an interesting idea. “I got in touch with the interpreters tonight so who knows what might come of it.”

Discussion