Plastic dissertation

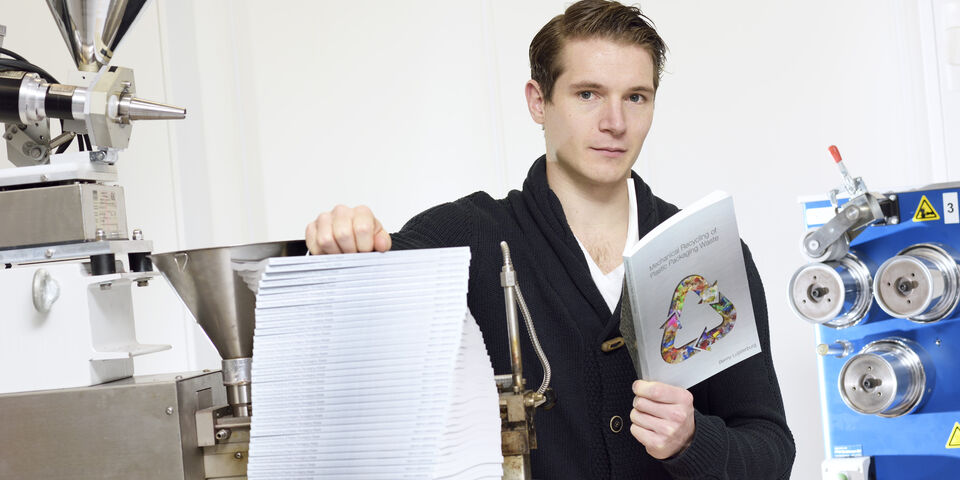

Plastic is more environmentally friendly than paper if we make an effort to recycle it. PhD candidate Benny Luijsterburg researched how to upgrade waste plastics to a high-grade raw material for new products. To assert his idea, he had thirty copies of his dissertation printed on plastic.

“As far as I know, this is the first-ever dissertation that’s been printed on plastic”, says Benny Luijsterburg. “But plastic is already widely used for restaurant menus, for example, because the material is water resistant and doesn’t tear easily.” The plastic used is fully recyclable, the PhD candidate explains. “That’s why it’s more environmentally friendly than paper, and it lasts much longer at that.”

Luijsterburg got his idea from the recyclers’ Bible Cradle-to-Cradle, which has also been printed on plastic. “I’ve investigated the material, and whether there were any Dutch printing houses willing to experiment with it. That’s how I ended up at Gildeprint eventually.” Considering the costs of printing on plastic are still about five times that of standard printing, the chemical engineer decided to have thirty of his 170 copies printed on plastic – special editions, if you will.

In these special editions – and in the paper copies, of course – he describes how used plastic packaging can be transformed into a raw material for high grade plastic products. Obviously, first steps include collecting and sorting plastic from the heap of waste – a process in which consumers (who throw away approximately sixteen kilos of plastic waste per person per year) play an ever-greater part by separating plastic from their other waste.

Untreated plastic is too brittle

Large part of this plastic consists of polypropylene, which is recyclable. Unfortunately, on average packaging waste contains five percent of another plastic: polyethylene. “It’s unavoidable. Shampoo bottles, for example, have caps that are made of a different material than the actual container”, says Luijsterburg. Separating polyethylene and polypropylene is a costly process, but the plastics don’t mix well either. And that’s a problem, he explains. “During processing, the polyethylene forms tiny globules, resulting in brittle material that can’t be used for just anything.”

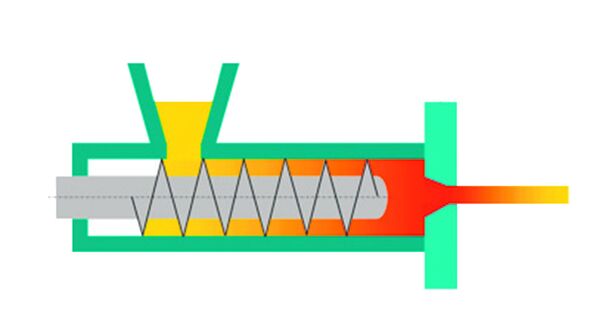

Better mixing turns out to be the remedy for the weakening effect of the polyethylene residue, the PhD candidate proved. For his experiments, Luijsterburg put the pellets of recycled plastic into a so-called extruder. The device is a sort of industrial mincer shaped like a long metal tube. Inside, a giant screw is spinning. The plastic pellets are moved through the extruder by the screw while the tube is being heated. The heat melts the pellets into a viscous liquid that is simultaneously mixed. After having passed through the extruder, the pellets have transformed into a kind of flexible spaghetti.

By adding an extra screw thread and positioning smartly-shaped obstacles in the extruder, the polyethylene globules break into much smaller lumps, so they are distributed among the material evenly. Luijsterburg calls it the Divide-and-Conquer principle, and it results in a much less brittle end product. “If you subsequently cool the liquid really quickly and under higher pressure, the plastic will even have a stronger crystal structure than it would otherwise.”

Stretching plastic strings makes them fifteen times stronger

Apart from experimenting with mixing and cooling, Luijsterburg has added soot, and filtered hard pieces of PET plastic during the extrusion process. But the most efficient technique, Luijsterburg proved, is one called drawing. Like all plastics, polypropylene consists of long chains of mainly carbon atoms. By stretching the cooled spaghetti from the extruder quite a bit most of these chains are oriented in the string longitudinally, making the spaghetti up to ten times more rigid and fifteen times stronger longitudinally. Similar stretching methods were known to be advantageous for new plastics, but it had never been tested for recycled materials.

As if he were an ambassador, the PhD candidate is currently trying to market his dissertation. “I want to contribute to a more sustainable society, so the industry needs to become aware of my findings: In a lab, I’ve proven that packaging waste can be made into high-grade plastic.”

The Netherlands harbors many, often small, businesses that focus on recycling plastic, he says. “All the companies I’ve talked to while writing my dissertation have received a copy and a letter explaining I’d love to come by to explain my results some time. There are too many dissertations that end up on a shelf and are only really read by the next one or two PhD candidates. I feel that because of the social nature of my work I’m required to pass it on to the industry.”

More environmentally friendly than paper

To promote the recycling of plastic, Benny Luijsterburg had thirty of his 170 dissertations printed on plastic. The plastic used is called Yupo® and is made of polypropylene – the same material the PhD candidate worked with, which is not only used for packaging, but also for garden furniture and car parts. He explains his choice inside the book: compared to a paper copy, production of the plastic special edition requires 2.7 times less energy, 17 times less water, and the emission of greenhouse gases is 1.7 times lower.

Discussion