- Research

- 11/10/2019

Nobel Prize rewards the development of rechargeable batteries

Where would we be without rechargeable batteries? The Nobel Prize in Chemistry goes to a trio of researchers who between them made the lithium-ion battery possible. They found materials that can efficiently store and release energy-carrying particles. TU/e professor Peter Notten says the Nobel prize is in recognition of the ‘entire battery community.’

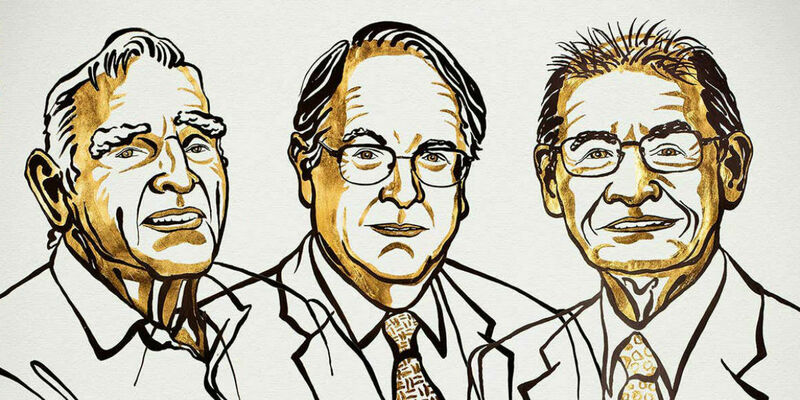

We live in a rechargeable world, says the Nobel Committee. From mobile telephones to pacemakers, batteries have become an integral part of society. And it is thanks to this year’s winners that they are rechargeable. The prize has been awarded to American John Goodenough and British American Stanley Whittingham and the Japanese scientist Akira Yoshino

Whittingham was involved with the early development of lithium-ion batteries in the 1970s. He developed a new battery cathode made from titanium disulphide, an effective material for housing lithium ions. Goodenough made the battery even more powerful by using a cathode of a metal oxide. In the 1980s, Akira Yoshino then improved the battery’s anode, making it safer and suitable for everyday use.

Peter Notten, professor emeritus at TU/e’s Energy Materials and Devices group, says it’s relevant that the Nobel prize has in fact been awarded to the ‘battery community.’ “Because a lot of people did indeed contribute small pieces of the puzzle that eventually led the invention of the lithium-ion battery. That also applies for this year’s winners: each one of them has made a specific contribution to the total design.”

Safely

In an email from Australia Notten writes: “What’s so special is the discovery of materials that can efficiently store and release energy-carrying particles. This way, the lithium-ions can be safely secured in guest materials. The English and American prize winners found several different guest materials that can be used as cathode. Their colleague from Japan made the entire battery system complete by also finding a guest material for the anode.”

This research has much social relevance, Notten believes. “Think of consumer electronics, for instance, that has really taken off as a result of the use of rechargeable batteries, and of lithium-ion batteries in particular. They are currently also being developed for electric cars, busses, bikes (transportation in general), and for future stationary applications in connection with Smart Grids as well.”

The prize amounts to 9 million Swedish kronor, the equivalent of around €825,000. Three Dutch citizens have been awarded this prize in the past. In 1936 the prize went to Peter Debye for his research into gases, electrons and X-rays. Paul Crutzen won the prize in 1995 for his research into the hole in the ozone layer. The most recent Dutch laureate of the Nobel Prize in Chemistry was Ben Feringa, who in 2016 was recognized for his work building tiny machines at the molecular level.

At 97 years old, Goodenough is the oldest Nobel Prize laureate in history. The previous record, which was set last year by physicist Arthur Ashkin, then 96 years old, has now been broken by several months.

Discussion