Every year the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) surveys the differences between the education systems in its member countries, from primary schools to universities. Things can always be done differently, is the organisation’s implicit message. In some countries students pay more, in others less. The number of young people who enter higher education also varies from one country to the next, as does government investment in education. The researchers have to collect data from around the globe, so the report is always a couple of years out of date and does not reflect the effects of recent policy.

Women

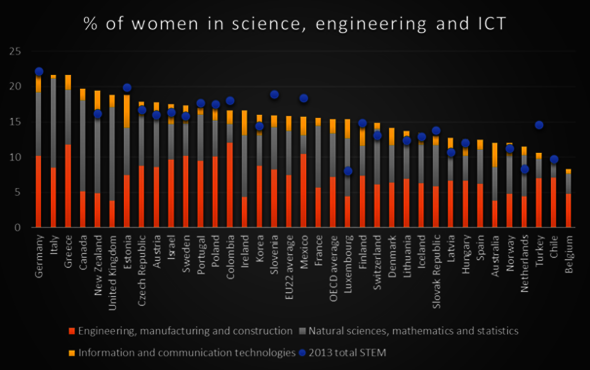

For example, the figures relating to women in science and engineering date from 2019. They are, however, interesting. For many years the Netherlands has been doing its best to interest students in STEM programs, and special recruitment campaigns specifically targeted at girls have been launched, such as Girls’ Day.

These efforts seem to have had some effect: in 2013 8.3 percent of female students entered a STEM program; six years later the figure was 11.5 percent. Nevertheless, the Netherlands is still virtually at the bottom of the list. Only in Turkey, Chile and Belgium do fewer girls go into STEM. (It should be noted, however, that in 2013 Turkey was still far ahead of the Netherlands.)

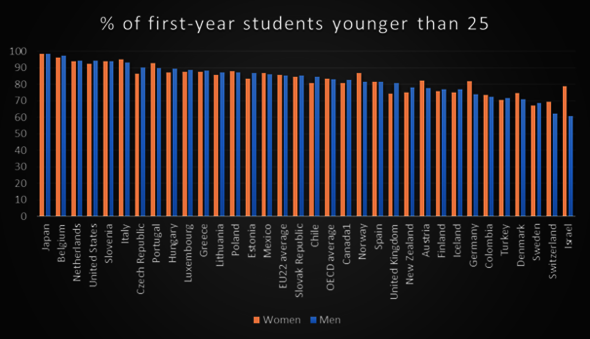

Other differences between the OECD countries stand out as well. In the Netherlands, for example, 94 percent of all first-year students (across higher education) are younger than 25, with no significant difference between men and women. Only Belgium and Japan exceed that figure. In Denmark, Sweden and Switzerland, on the other hand, the figure is less than 75 percent. In Israel there is a remarkable difference between men and women.

Naturally the writers of the report have also tried to take the consequences of the coronavirus pandemic into account. To do so, they calculated how many teaching days were lost (relatively few in the Netherlands) and looked at the measures that were taken by governments.

But, as already stated, the report is a little out of date. A summary of support measures shows that, unlike most countries, the Netherlands has provided no extra funding for education. The billions under the National Education Programme came just too late for the OECD.

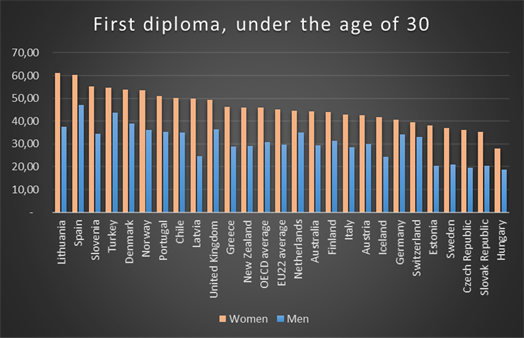

Bearing in mind these shortcomings, the less time-bound information is all the more pertinent. What percentage of men and women get their first higher education diploma before they reach the age of 30? Across all OECD countries women tend to graduate before their male peers, but the difference is smaller in the Netherlands.

But what constitutes higher education? In other countries educational programs are sometimes included that would be classified as vocational training (MBO-4) in the Netherlands. There are also differences in the duration and quality of educational programs.

Education expenditure is always a sensitive topic politically. The OECD looks at this as well, but it is even harder to make comparisons in this area. The report shows, for instance, that the Netherlands has increased its budgets for higher education but that the economy grew more quickly than the investments in education. So were those investments sufficient? To a certain degree the figures are open to interpretation.

But in the view of the Netherlands’ education ministers, making the comparison is still worthwhile. “On the basis of the OECD figures we conclude that, in an international comparison, the Dutch education system scores well on a variety of indicators. But we also conclude that improvements are both possible and necessary”, they write in a memo to the House of Representatives.

Discussion