Home Stretch | Valuing employee talents

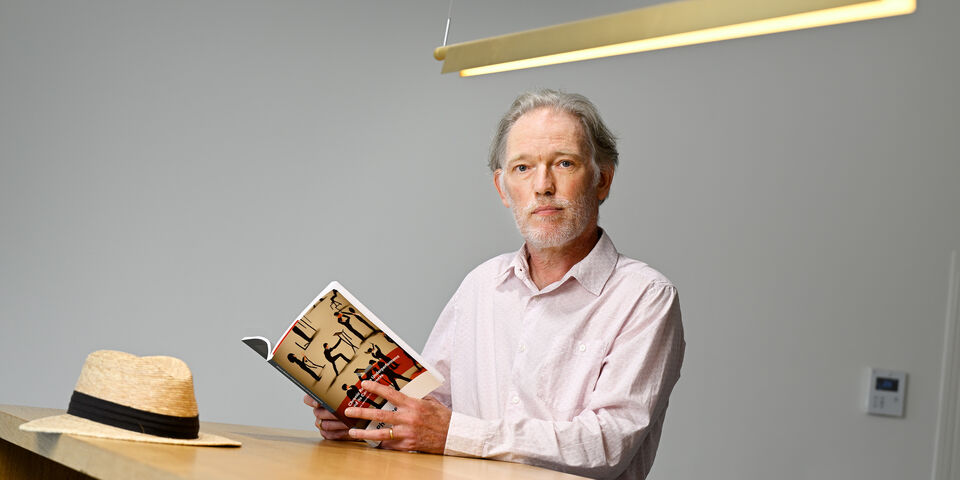

Employees often possess a wider range of talents than they need for their jobs; for example, they may be musically gifted or have great visual thinking capabilities. If these capabilities are not seen and valued, there is a higher risk of what PhD candidate Haiko Jessurun calls “chronic relative underperformance” (CRU). For his doctoral research at the Department of Industrial Engineering and Innovation Sciences, he investigated this phenomenon and how CRU can affect employee performance. Today, he will defend his dissertation.

Jessurun has worked as a child and adolescent psychotherapist and clinical psychologist for more than 30 years. Throughout his career, he has worked with high-gifted dropouts. “These were young people with many talents and capabilities, who still failed to perform to their full potential,” he says. According to him, they were often not seen for who they were and what they were capable of. He calls this phenomenon chronic relative underperformance. “And it makes you sick,” he hypothesizes.

Mentalization

“When people don’t feel seen, something happens to them,” he continues. In psychological terms, we call this “being inadequately markedly mirrored”. By being mirrored markedly, you discover who you are and learn to mentalize. “Mentalizing is the ability to imagine what is going on inside another person, but also to know what motivates your own behavior,” he explains. “If you’re not mirrored markedly, or inadequately so, you can end up developing a strong belief of: what I do doesn’t matter anyway, I’m not valued so there’s no point. This can lead to problems in the long-term and may even incapacitate you.”

“At a certain point I thought: if even children experience problems because of this, it means that adults who don’t feel seen can also get stuck,” he continues. His basic assumption was that talented people cannot thrive in a work environment in which their full potential, including all their talents and abilities, is not seen and valued. Almost a decade ago, Jessurun decided to delve deeper into this topic, and thus he began his doctoral research, in his spare time alongside his job as a clinical psychologist and psychotherapist.

Relative underperformance

“Employees often possess talents that are not directly related to their job but can still be very useful,” he explains. This leads to a mismatch between the individual and their work environment. In this situation where employees cannot make optimal use of all their talents, they are relatively underperforming, according to Jessurun. In terms of the job requirements and from the perspective of the employer (or their own perspective), they perform satisfactorily, but when compared to what they are capable of or, in other words, in relation to their capabilities, they underperform.

When their talents go unseen for a prolonged period of time and the work is not geared towards these talents, we speak of “chronic relative underperformance” (CRU). This is a term coined by Jessurun which he uses in his dissertation. For his doctoral research, he examined this phenomenon and the central question he posed was: how does chronic relative underperformance affect employee functioning? His hypothesis was that CRU can have a negative effect.

Multiple intelligences

To get an overview of the full range of people’s talents, Jessurun used psychologist Howard Gardner’s theory of multiple intelligence (MI). This differs from the traditional concept of intelligence measured by an IQ test. An IQ test assesses an individual’s linguistic, mathematical and spatial abilities, and the standardized score gives an indication of a person’s cognitive abilities. Gardner believed this definition of intelligence to be inadequate and described different types of intelligence, including musical, interpersonal and physical intelligence.

“Some people have a fairly balanced skill profile; for others, some types are much more dominant than others,” the PhD candidate explains. “Because of the specific criteria that a particular intelligence must meet, it is safe to say that the currently identified intelligences cover all categories of skills or talents a person needs to solve problems, provide services or make products.”

Based on the eight categories of multiple intelligences, Jessurun developed a questionnaire to identify job profiles in MI terms which he used at a mental health institution. In order to identify personal profiles, he translated and used an existing questionnaire, the MIDAS®. Survey data were then collected from an addiction treatment facility.

Ultimately, over 140 MI profiles were obtained. He then compared the job profile with the personal profiles to see how much of a (mis)match there was between the person and their work environment. “If a person scores much higher for certain skills than is required, there is a higher risk of chronic relative underperformance,” Jessurun argues. His next step was to see if there was a relationship between this risk of CRU and the performance of these employees.

Sick leave

The studies show that CRU has a negative impact on the frequency and duration of sick leave among employees, productivity and perception of the organization. For some skill categories, the influence of CRU seems to be greater than for others. “For example, employees with higher musical intelligence are sick slightly more often and slightly longer and also somewhat less productive,” Jessurun demonstrates. The results of his study show that chronic relative underperformance negatively affects various aspects of employee functioning. As such, he argues that employers and employees should be more mindful of talents across the spectrum and how they can be utilized.

He says more research is needed to confirm and expand upon these findings. “Of course, it will also be necessary to start researching how to prevent the consequences of CRU.” He believes management, HR and employee coaching could play an important role in this. “You can come up with all kinds of possible solutions, but the very first step is to become aware of relative underperformance and what it does to people,” Jessurun says. “Its important to see and value people for all their abilities and talents, not just as machines to perform a task. As such, focus on CRU is a tool that can be used toward the humanization of organizations.”

Discussion