- The University , Education

- 06/10/2022

Lots of funding for higher education, but there’s always room for more

The Netherlands ranks among the top ten countries that invest heavily in higher education, a new OECD report shows. But the education ministers insist that the Netherlands belongs in the top five. Perhaps that would help attract a few more lecturers.

On Monday, the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) published its annual report Education at a Glance, this time with a special focus on higher education. According to the report, the sector needs to adapt now that so many young people are entering higher education.

Student numbers are continuing to rise in all 38 member countries. In 2000, only 27 percent of 24 to 34-year-olds had a degree from a university or a university of applied sciences, compared to 48 percent in 2021. Higher education institutions must therefore cater to an increasingly diverse group of students.

A higher education degree seems to have become the new norm everywhere, and this is having an adverse effect on vocational education. The report argues that some students would actually be better suited to vocational education, but they will only take this path if vocational programmes are made more attractive, not least by strengthening links with higher education. These students should also be given the opportunity to continue their studies later on in life.

Investment

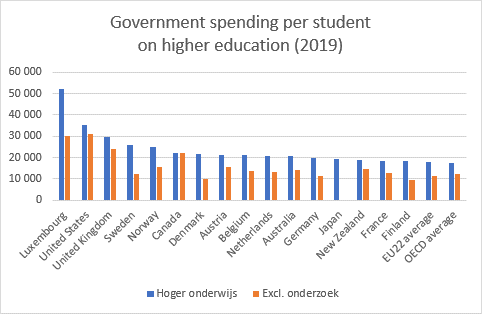

The report also contains many comparisons that shed light on the different choices made by the member countries, such as how much a country is willing to spend on higher education and research. The Netherlands is among the top ten, spending more money than average.

“However, we are not in the top five,” education ministers Robbert Dijkgraaf and Dennis Wiersma write in response to the OECD report, “and that does not reflect our ambitions.” The ministers expect the additional investments recently announced by the government to remedy this situation.

Mr Dijkgraaf explained that the additional spending is needed to ensure that the growing student numbers do not have a negative impact on Dutch higher education. The minister also reiterated that he will look for “new instruments to control student flows” in response to the large number of international students coming to the Netherlands.

Stress

A new form of the basic student grant will also be introduced. Given the high number of Dutch students now working alongside their studies, there appears to be a real need for this change: 47 percent of students have part-time jobs, compared to the average of 17 percent for OECD countries. In addition, a relatively large number of students are taking longer to finish their education, although most of them do eventually graduate. The ministry is taking these findings on board in a new study on performance pressure and stress among students.

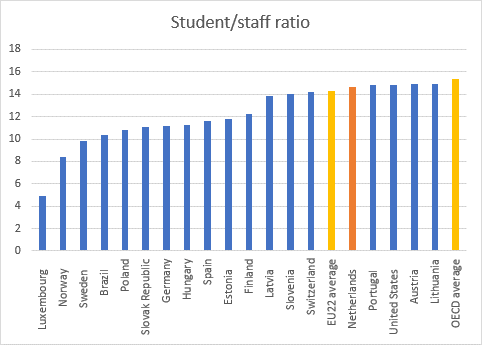

The workload among lecturers is also relatively high in the Netherlands. On average, one lecturer teaches 15 students, putting the Netherlands a little above the OECD average. On the other hand, the higher education workforce is relatively young.

Deficit sectors

The OECD also looks at what is happening in the labour market. This reveals that Dutch graduates are well placed when it comes to finding a job. Of those with a higher education degree, 91 percent are employed, well above the OECD average of 85 percent.

The Netherlands does, however, have some persistent ‘deficit sectors’. Only 12 percent of students pursue a STEM degree, compared to 16 percent on average in OECD countries.

Discussion