Spatial and temporal delocalization of work

At the start of the lockdown in March, my big concern was the uncertainty around work. My household was reasonably precautious about COVID, but like most, I was inexperienced in working from home, especially when it’s not optional and indefinite.

The first issue was the environment: sharing a house was incredibly favourable during a lockdown, but I feared the mild distractions that came with it.

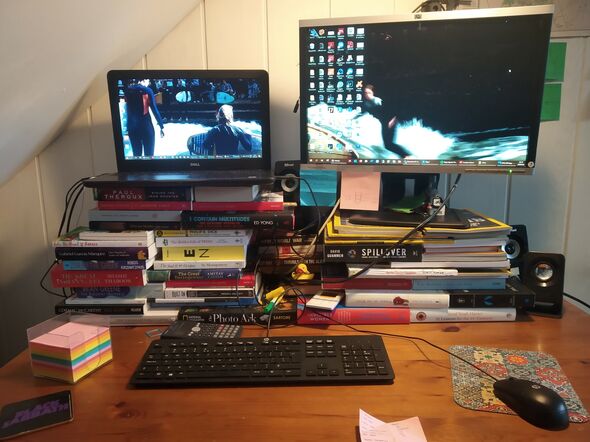

The second was infrastructural: wonky internet, a flimsy desk, data availability, absence of a printer, the remotely accessed computer in the office wanting to restart every now and then. Social scientists worldwide would study these elements for decades, perhaps. But one bookshelf emptied onto a desk and some ICT guidance later, it became workable, sort of.

As the weeks went by, however, it slowly hit me that whatever work was manageable from home started to spread out over the course of the day. The slow afternoons, sometimes spent indulging in a sunny backyard lunch or anxiously watching the news, may have played a part, but it was the changed nature of tasks that made a bigger difference.

Reading, writing and taking up courses were pretty much all that an otherwise 100% experimentalist could do. And it doesn’t take long to realize that these things happen almost as effectively (or otherwise) in the evenings as during the day. But I accepted the balance of my new abnormal as it came and it worked out reasonably well, for a while.

The partial opening of the laboratories in May first threw me off my footing. Work-shifts meant that the shorter assigned times had to be used to the maximum, planned and executed with impeccable precision. The pace quickened and the frenzy around equipment grew over a few months.

It also meant that the traditional deskwork (reading, writing, processing data) got relegated to the home office where the dynamics remained mercifully relaxed and consequently significantly longer. This isn’t new, people worldwide are experiencing similarly long workhours during lockdown. Where the distinct line between work and home first blurred in March, it had disappeared altogether for me by late May.

As things seemingly got better on the COVID-front followed by a more liberal opening of the university, an unexpected factor kicked in. It stemmed from the restricted office occupancy policy (one person per a typical office in my building) while the opening allowed an unrestricted access to employees, consisting of a high proportion of experimentalists, kept from their natural habitat for months. How does one square that circle?

We ran out of workspaces within the first few days as employees and students flocked in. My group arranged for temporary workstations in vacant rooms and eventually in lab areas. It helps that only last October, we had relocated to a larger lab-space, so equipment is relatively spaced out and there was some additional room available. Nevertheless, for the last few weeks, it isn’t uncommon to find colleagues waddling about corridors hunting for a place to set up shop because their usual spot is already occupied.

The pandemic has exposed quite some gaps in how institutions, and society in general, perceive work. But it’s also forcing a sort of evolution on that front. Quite a few companies, for instance prominent tech giants, have toyed with the idea of indefinite work from home formats even when lockdowns relax.

There is some debate around the nature of permissible migration that many regularly undertake for employment. But I have the feeling that in many cases, we lose cognizance of the fact that work and the value of time in that respect no longer has the same meaning as it did before. A recalibration of expectations might help, but that seems unlikely if the goal itself is to go back to the old normal instead of fashioning something reasonable out of the current abnormal.

Discussion