Drones pose threat to aviation: "European approach needed"

TU/e researcher wants to convert car chips to detect drones at very short range

Copenhagen, Oslo, Warsaw, and Munich have something in common: problems due to unexpected drones at their airports. The technology to detect them is lagging behind, and European regulations for shooting them down are still lacking. TU/e researcher Ulf Johannsen believes converting car chips may provide part of the solution needed.

Drones flying around international airports were a frequent issue this fall. They pose a serious risk to aircraft. Such a drone could, for example, get into an engine. Or, in the case of a hostile drone, carry an explosive.

In Copenhagen, air traffic was repeatedly halted for a time after the drones were sighted. But why weren't they simply shot down? Danish authorities indicated that the risks were too great: if the debris land, they could injure people.

Detecting the drones is not easy. Existing airport radars are focused on the airspace because that's where the airplanes are located. They can detect drones when they are still relatively far away and high in the air.

If the drones come closer or fly low to the ground, the radars lose them. Drones can also quickly take off and land again. The characteristics of the drone and the mismatch with the airport radars make it difficult to find the person or organization behind them.

Shooting down drones is also somewhat unconventional from a financial perspective, says Ulf Johannsen, associate professor and director of the Center of Wireless Technology. He specializes in antenna systems.

A drone is very cheap, a missile very expensive. "Air defense has so far focused on shooting down very expensive aircraft, because that means a greater financial damage to the enemy. Now we have to rethink and find a system for very cheap drones. Such a solution shouldn't be more expensive than what you shoot down."

European cooperation

Besides the dangers of shooting down drones and the financial implications, there are also no clear European regulations on how to intervene.

Currently, countries can still establish their own guidelines for shooting down drones. Some countries stipulate that aircraft pilots must have seen the drone threat with their own eyes. In other countries, shooting is permitted upon detection on radar.

European countries share NATO airspace, so an effective response to an attack will require cooperation. Within the EU, there are 32 defense ministers, each with their own opinion on how to approach this. Therefore, it won't be resolved overnight.

Military requirements

Rules that must be established across the EU are so-called military requirements, which are kept secret to avoid playing into the hands of the enemy, who could then tailor their actions accordingly.

Johannsen understands this secrecy, but also sees a problem. "If knowledge institutions, companies, and governments are not allowed to know the military requirements, we cannot build a solution together. To develop one, you need to know those preconditions."

Detection system

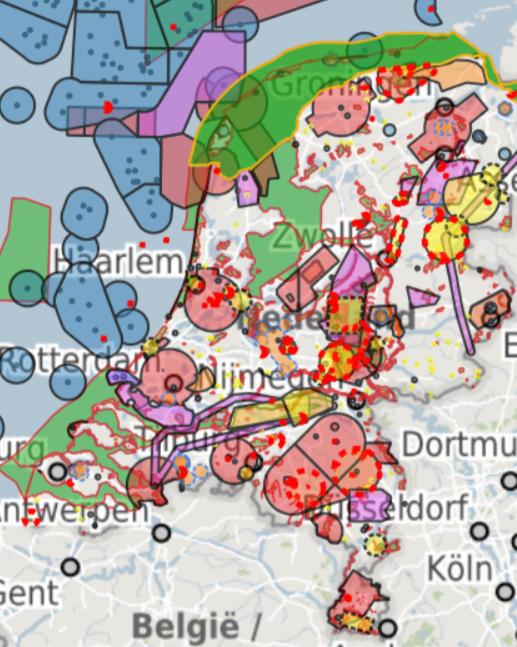

Researcher Johannsen does not specialize in air defense, but he does have clear ideas about developing effective drone detection. He advocates appointing a driving force — for example, from the government — to address the drone problem. Johannsen believes that the Netherlands can provide part of the solution that could ultimately also be deployed in other countries.

"We have all the equipment in the Netherlands to build a drone detection system. With radar manufacturer Robin Radar, there is also an industrial player that builds such systems." However, existing chips must be modified for very short-range drone detection.

"Short-range drone detection is essential for every military vehicle, for example, when a tank needs to neutralize a drone. To achieve such a system, we also need someone to coordinate the development and production process."

Adjustments

Johanssen believes the government needs to talk to CEOs from the private sector to solve this problem. "Or someone from the Ministry of Defense needs to take this role due to the sensitivity surrounding the military requirements. But something needs to be done."

What he believes is absolutely necessary to get a detection system off the ground is understanding the military requirements. After that, a chain of partners is needed for the development and production of drone detectors. Consider, for example, a company that makes radar chips and can adapt them, a partner that supplies a signal booster, a knowledge institution that can use chips in short-range drone detection, and a company that installs the solution in, for example, military tanks.

Where do the drones come from?

Fingers are pointed at Russia as being responsible for the drone plague at European airports, but can we be certain? Drones can be controlled in many different ways: remotely, for example via Wi-Fi or 5G, or directly via fiber optic cable.

One possible scenario is that the drones take off from ships at sea. Russia has previously been spotted in Scandinavian waters, often even under a different flag. But while that may sound suspicious, the country is not alone in this.

At the same time, individuals can also launch drones. This is not permitted in no-fly zones such as those at airports. However, perpetrators are difficult to catch because drones have a long range and are often only in the air for a short time.

Fiber optics

Wireless control of drones (via Wi-Fi or 5G) occurs on known frequencies. An airport can choose to place antennas near the fences that transmit a stronger signal on those same frequencies, so that the drone can no longer ‘hear’ flight instructions. But even then, malicious actors already have an answer: fiber optics. A very thin, lightweight fiber optic cable is attached to the drone, allowing it to fly up to 30 kilometers. That's enough to fly from an aircraft carrier off the coast to the airport of Copenhagen.

"The same is possible from land: a fiber-optic-controlled drone can approach from miles around without being disrupted by nearby signals," Johannsen adds. And the fiber optic cable through which it receives the communication is so thin and virtually invisible that it's difficult to hit.

Dutch expertise

In the Netherlands, we are well-equipped to build a drone detection and defense system, Johannsen believes. "We have companies with the necessary expertise, such as radar manufacturer Robin Radar and electronics company Thales. But we also already produce automotive radars that can be adapted just with minor modifications to detect drones. 'Radar expert the Netherlands' should be able to do this."

To explain the technology, Johannsen gives an example of a successful project in which his group built a radar — based on 5G technology — that tracked flying objects. "We used existing 5G chips in a different way."

He shows a prototype used in that project. "The electronics in it were designed for 5G antennas and are much cheaper than similar chips used by the Ministry of Defense." However, he notes that it's sometimes difficult to market such adapted ‘out-of-the-box’ ideas.

"Governments often have long-term roadmaps for purchasing materials." It's then difficult to convince them to stop midstream and choose a new solution that's still relatively unknown.

Discussion