“I don't like the word refugee”

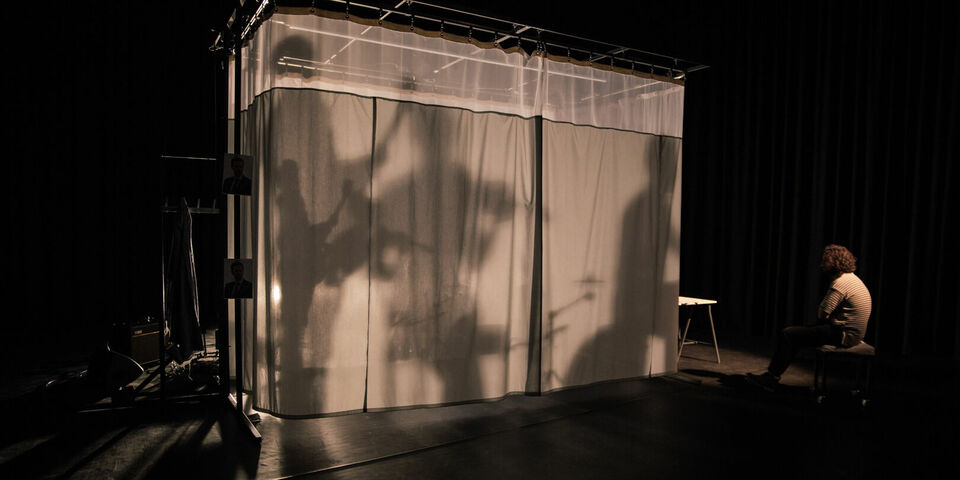

A theater production about hope, courage, faith and disbelief - that say the makers is ‘Children of Aleppo’ in a nutshell. The piece (to be seen on TU/e campus this Wednesday evening) tells the story of three students who took to the streets to gain greater freedom in Syria, where the people's peaceful demonstrations were destined to culminate in a devastating civil war. As a student of architecture in Aleppo, TU/e student Alaa Alden Alhamad experienced the war at first-hand.

Alaa Alden was born and raised in Damascus, the Syrian capital, but anyone who asks him where he comes from is told: from Aleppo - because that is the city where his parents come from. And the city where he went to live at the age of nineteen as a fresh young student of Architecture at the University of Aleppo.

His first year there was peaceful, he recalls. But on March 15, 2011, having coursed through the region for a couple of months, the Arab Spring movement reached Syria. Not at first in Aleppo, but elsewhere in the country citizens started to rebel against the regime of president Assad. A dictator who held everything and everyone in his grip, as Alaa Alden himself sees it - a view he believes is now shared by the majority of Syrians.

“In Syria people rebelled as they had elsewhere, driven by the need for more freedom, greater scope for expression. In the Netherlands you can be critical of, say, the government, of politicians, and you can express your criticism. That's inconceivable in Syria; anyone who speaks out against the regime runs the risk of being arrested and imprisoned. People were rightly afraid, but when they saw what was happening in Tunisia, for example (where the government fell following mass protests, ed.), they had the feeling: ‘We can stand up together just like they have’.”

Excitement

For the most part, Alaa Alden was gripped by a feeling of excitement, he says, born of the hope for change. This feeling was particularly strong when people in Aleppo joined the protest, which stemmed initially from his own university. Students, himself included, expressed their support, mainly via social media, for the insurgents in other cities, and wrote signs: ‘We support you’. It wasn't long before the police targeted the university: “Stop this or you'll be arrested”. The students were given a warning, “actually only because there were so many of us. Otherwise they would have arrested us right there and then.”

He recalls how not long afterwards two classmates were indeed arrested, and how the dean of his department first reacted by tapping into her networks to get them released. “But she also warned us, ‘I understand what you are doing - but this isn't Europe’.” Not long after that the police raided the department, says Alaa Alden, “looking for people who they didn't find on that occasion. But to send a message they destroyed windows and doors.”

In 2013 the situation in Aleppo became “serious”, says Alaa Alden. President Assad's army entered the city; according to the student, “trained to kill”. Fights broke out between the government army and the insurgents, at one point right outside the student's door. His family, who were living just outside Aleppo, urged Alaa Alden to leave the city, but he didn't want to. “Architecture's fantastic, I was in my third year, and on the campus everything seemed normal. It seemed to me that my study was the only thing allowing me to escape a little bit from the violence going on every day in the city.” But deep down he knew: “My family were right”.

Read on below the video.

So he did go to live with his family after all, putting his studies on hold for a year. In 2014 he returned to Aleppo. “I was bored. I had work but my heart wasn't in it.” Under wretched conditions, on a half-abandoned campus surrounded by the violence, Alaa Alden completed the fourth year of his degree program.

The risks were great. Alaa Alden often felt unsafe and admits that “there were a couple of close calls. Soldiers in Assad's army stopped me one time, for example, and wanted to check my laptop. They would certainly have found something on it, via my contacts with friends, had it not been for the fact that right then a professor walked past and said, ‘He is one of my students. Come, we have a lecture now’. I escaped, but it could easily have ended very badly.”

Islamic State

When Islamic State (IS) joined the conflict in Syria in 2014, his father decided that the family had to leave. But while his family left for Turkey and his father subsequently ended up in the Netherlands, Alaa Alden stayed behind in Aleppo. “I wanted to finish my degree.” This continued until his father submitted a request for family reunification to the Dutch government and his family then had three months in which to report to the Dutch embassy in Turkey.

Read on below the video.

Having just started his final year of study, Alaa Alden, persuaded by his father's encouraging impressions of the Netherlands, decided to leave Aleppo. Although he talks about it with apparent calm, getting out of Syria (by bus, with a larger group) was anything but easy. “We had to pass through various controlled areas; one in the hands of Assad's regime, another controlled by IS, the third one by the insurgents. At the checkpoint run by the Syrian regime they wanted money. I think I paid about a hundred euros; a huge amount of money in Syria.”

He continues: “Above all, you had to manage to persuade people that you weren't involved with any of the warring factions. But IS regards you with suspicion no matter what. That passage was the most dangerous. They wanted to know who I was, where I was going. I didn't say I was going to Turkey, but to Idlib, the last city before you enter Turkey, to stay with family. Yes, I was scared. It was insane. I had my laptop with me, my cellphone. Valuable items, that they often confiscate straight away. But I managed to hide them. Then I was allowed to go - but not without a threatening message: ‘We don't want to see you here again; you know what will happen if we do.’”

People asked, ‘What are you going to do in Venlo of all places? That's where Geert Wilders comes from’

At the border with Turkey, Alaa Alden and his travel companions had to take their baggage off the bus and walk the last part on foot. After travelling for three-and-a-half days, he was reunited in Turkey with his mother and his younger brothers and sisters, all six of them. Whereas he had remained outwardly calm until that moment, the reunion unleashed his emotions. As did the realization: “I am safe”.

Welcome

After spending two months in Turkey, the family flew to the Netherlands. His father was then living in Utrecht, later the family moved to Venlo. “People asked, ‘What are you going to do there of all places? That's where Geert Wilders comes from’. But it was okay.” Nonetheless, after a year Alaa Alden swapped Venlo for The Hague. Via his neighbor there, who was already studying in Eindhoven and who arranged an introductory interview for him, he ended up at TU/e. Delft may have been closer to home, but the command of the Dutch language that was required there discouraged him. “In Eindhoven they put the emphasis on having a good command of English.”

UAF

According to figures issued by the Foundation for Refugee Students (UAF) some seven hundred students who have fled Syria are currently studying at a Dutch university of applied sciences or university. The UAF is supervising nine students of Syrian origin at TU/e, among them Alaa Alden.

The foundation - which is able to do its work thanks in part to donors - supports and supervises refugee students in various ways; for example, by helping them find a suitable study program and fulfill any admission requirements it may have (such as a command of the Dutch language). In cooperation with other bodies such as municipalities, the UAF can also help newcomers secure funding for their study when they are not (or no longer) eligible for student financial assistance. The foundation also offers supervision on the pathway to employment.

In total eleven students of Syrian origin are studying at TU/e : ten are doing a Bachelor's program, and one a Master's program, as figures issued by Education and Student Affairs reveal. Five of them started their program this year, four in 2017, one in 2016 and one in 2015.

And here he is, having arrived this past September, in the third year of his Bachelor's in Architecture, Building and Planning. The Hague remains his home, “that's where my friends are; Dutch and international”. He says he has always felt welcome in the Netherlands. “Of course, online I see different reactions. But among the people I've encountered, I've never had the feeling that anyone wanted to get rid of me.”

Half Dutch

People rarely ask him about his Syrian roots or his experiences, says Alaa Alden. However forthright the Dutch usually are, they approach these matters with caution, he thinks. “For my fellow students I am simply an international, one who happens to come from Syria.” Although first and foremost he feels himself to be “half Dutch, can you get Dutch citizenship only after five years. But I feel increasingly that I am a part of Dutch society, I can chat a little bit in Dutch, I am starting to understand the mindset better.”

Although he doesn't envisage returning for good, he still carries Syria in his heart, “I lived there for twenty-three years, it will always remain a part of me.” A newcomer is what he prefers to call himself - not a refugee, “I don't like that word. We didn't choose to leave, we were forced to.” But more than anything he wants to focus on his new life here. “If you get stuck thinking about where you come from, you can't move forward here. The word ‘refugee’ refers back to Syria, ‘newcomer’ refers to here.”

As a result, he doesn't think too much about what the country of his birth has been through. Not that he has much time to do so. “Dutch life is busy, the diary is very full. It's better that way. If I had nothing to do, thoughts would surely come.”

Alaa Alden preferred not be photographed for this interview.

Children of Aleppo

TU/e's Studium Generale is hosting a Dutch-language theater performance entitled 'Kinderen van Aleppo' (Children of Aleppo) on the evening of Wednesday November 21. This is a live, solo performance by George Elias Tobal - who himself fled Syria. The production, produced in cooperation with the Foundation for Refugee Students (UAF), is based on the true stories of students who were involved in the early protests. For more information, check out the SG site.

Discussion