CursorOnTour@CE&C | Bert Meijer: “My intermezzos provide the chemistry”

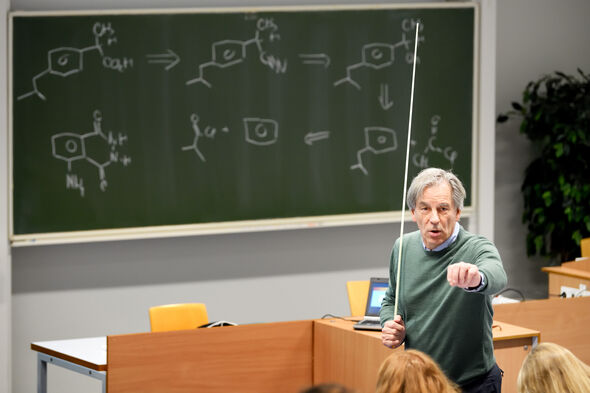

The science is over my head, I'm a reporter not a chemist, after all, but I do understand why it's fun to attend a lecture given by Professor of Organic Chemistry Bert Meijer. He follows his students' line of thought, makes a personal comment now and again, and twenty minutes into every lecture hour he holds an intermezzo. But what he chiefly does is present the fundamentals of organic chemistry as often as he can in new and different ways. Repeat, repeat, repeat.

The students (roughly eighty second- and third-year chemistry students, the odd BMT student) have arrived on time, after all Bert Meijer starts at 9.45 a.m. sharp. They aren't reaching for a laptop, but for pen and paper. This is their twelfth lecture on organic chemistry. “A regular basic course, but it has to be said one of the finest basic courses in chemistry,” according to Meijer.

Today he's talking about molecular design and retro-synthesis. His first sentences are about the chemist Wöhler who synthesized urea in 1828. In rapid tempo, he runs through the first 150 years of carbon chemistry.

Yellow card

Not five minutes have passed before he interrupts himself. “Hey, hey, hey,” and he points with his stick to a student. “Yellow card.” During the next two hours the student doesn't glance at his telephone again. Nor does Meijer have to ask for his students' attention.

Then he tells his audience the aim of this lecture. Today is all about retro-synthesis. “In a retro-synthetic analysis you disassemble a molecule and you try to synthesize it by reviewing how you broke it down. Step by step, or in bigger chunks. How is this molecule constructed?”

He gives an example involving an acid and asks the students a simple question. The room is silent. Meijer gives some encouragement. “You know this from a previous lecture.” Cautiously, a guy gives an answer, but only the start of an answer because it's Meijer who heads the ball into the net.

The lecture is in English, but just once he goes off piste: “A quick aside for the Dutch speakers among us: scheikunde is about the kunde (skill) of het scheiden (separating) components.”

Artificial Intelligence

Meijer is a visionary who likes to tell his students how chemistry is going to develop. “I am too old to use artificial intelligence, but you are going to see AI being used in retro-synthesis within the next ten years. Make sure you learn about it. Don't miss that boat.”

He is critical of some parts of the otherwise excellent textbook his students are using. “The way retro-synthetic analysis is presented in your book there is dumb. At any rate, ignore this first section. Don't use this. I can't stand how it is described here. Please pay attention to my explanation instead.”

Precious little material comes out of the blue. Meijer repeats himself and places new information in a context. “What you have learned so far about substitutions, additions and eliminations in synthesis was quite simple. Today we'll go into it in more detail.”

Intermezzo

The professor who has bagged the Nagoya Gold Medal of Organic Chemistry brings current events into his lecture. “I saw on the Dutch evening news this weekend that a molecular spray has been added to the tear gas used by the police in Paris. A week later, with UV rays, the molecules can still be seen on the rioters, even if they have washed their hair. Very expensive stores also use this spray.”

A personal note: “I never visit chic stores. But when I looked that up I also came across the substance luminol, which is used to discover traces of blood; blood contains an oxidant that makes luminol start to glow. You know what I mean, it's in those light sticks you can snap to get colored light for a couple of hours. When I was your age we used them at pop festivals. Sound familiar?"

The aside about luminol was one of Meijer's famous intermezzos. “It's something I've been doing for the past twenty-five years,” he tells me in the break. “Every lecture hour, after twenty minutes, I talk about something in the news or about a recent publication in Science or Nature. It sometimes takes me more time to prepare this than it does to put the lecture together. I also use them to manage my time. If I'm running out of minutes, they get shorter; if I have time over, the intermezzos get longer.”

Every lecture hour, after twenty minutes, I talk about something in the news or about a recent publication in Science or Nature

Like the French language

In the same breath he explains what bothers him about the curriculum these days. “When I was a student, I had two hours of organic chemistry every week throughout my entire Bachelor's study. Now students have to cram it into a single quartile and afterwards they hear nothing said about it for a very long time. Repetition is so important. So what I do is keep on presenting the material they already know, always in some new way.”

He compares chemistry with the French language: “There's vocabulary and grammar. If you've learned all that stuff but haven't put it together and used it for a year, your knowledge isn't going to be of any use on a holiday in France. In chemistry you have molecules and bonds, and they are what you have to learn to ‘speak’ with.”

Meijer keeps the students engaged: “This is easy, after all, it isn't the first time you've had a lecture on organic chemistry, is it?” Or, “This is difficult; I too need to take a moment to think about this. How long is an exam? Oh, then you'll have plenty of time.”

He sees who is sitting in the lecture theater. Notices who is about to ask a question. Calls on someone to speak who won't find the experience disconcerting. “I see some faces that don't remember this…” He quickly writes his formulas on the board. I could do with the 2 being a little less like the 3 and the R could be a little clearer, but the students aren't complaining.

It's best to pay attention

Sometimes the intermezzos appear spontaneously. Suddenly the talk has turned to ecstasy pills in Brabant. “Remind me again what the famous words are if someone asks you to make ecstasy pills?” he asks. A student replies, “Reductive amination." Then, on the board he makes it clear that you should never get involved in reductive amination outside the TU/e lab.

He refers them to a question sure to come up in the exam on the Robinson annulation. “Thirty percent of students get that wrong. It shows me whether you really understand the molecular language and whether you've been paying attention during this lecture.”

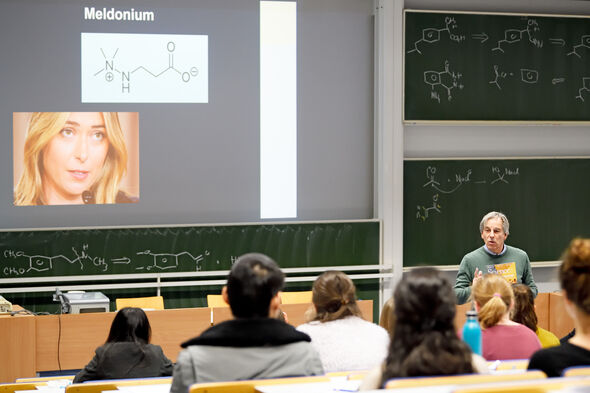

And then it is time for another intermezzo. Students recognize tennis star Maria Sharapova. She has been accused of using meldonium, but is now back on the tennis court. Meldonium is an example of retro-synthesis. It's mentioned in the latest New Scientist. “You should read it! In its pages Ghislaine Vantomme and I make it clear how you should go about doing non-covalent synthesis - we are proposing a paradigm shift. How will you be able to make life in a lab one day? That too is in this week's Science.”

After two hours, Bert Meijer concludes his lecture with a short summary of his aim. “You have now learned how a molecule is designed, how you can apply functional groups and how to make carbon-carbon bonds. See you next week.”

Impressive lecturer

Jolijn Braun (student of Medical Sciences and Technology) tells afterwards that this lecture is representative. “It is similar to his other lectures. He provides clear explanations. He covers simple stuff quickly and he uses his time to give a lot of examples. That's how you really learn something. I can see he puts a lot of effort into his preparation and that he is still enthusiastic about his field. I really enjoy the intermezzos. He uses them to link the material to the real world, and that makes everything less abstract.”

Jolijn doesn't have any 'points for improvement' for Meijer, and she's even learned to read his handwriting. “As a chemistry student you know that the figure relating to a bond is a 2 and not a 3, it just has to be.” She does think, however, that the interaction with the student group is less than optimal, but she admits she's partly to blame. “I offer few answers myself. He invites us with ‘come on, you know it’. But that just makes me doubt whether I know the right answer and so I don't say anything. You don't want to make any mistakes, especially not in front of a such a first-rate scientist. And I bet other students feel the same way. Perhaps we feel a little intimidated.”

This article is part of the special CursorOnTour@CE&C series, with on-site reporting, this time from the department of Chemical Engineering and Chemistry.

![[Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/8/a/csm_BvOF_Bert_Meijer_college_3_c3e37ebe99.jpg)

Discussion