- The University

- 12/10/2022

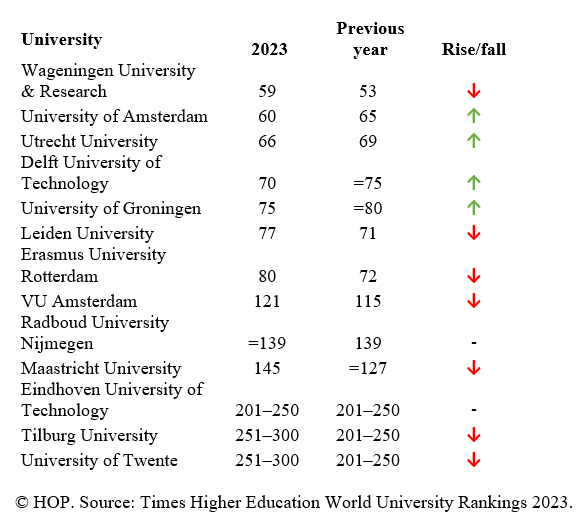

According to the British ranking, ten Dutch universities are still among the best two hundred in the world. Only five countries have more universities in the top two hundred: the United States, Britain, Germany, Australia and – for the first time – China.

For the second year in a row, the TU/e is not in the top-200. The university is part of the segment from 201 to 250. Last year, the universities of Twente and Tilburg were also ranked there, but they now both are in the group from 251 to 300.

The wide-ranging assessment includes academic performance, reputation in education and research, internationalisation, the number of students per lecturer and collaboration with the corporate sector.

Front runner

The front runner among the Dutch universities is Wageningen University & Research at no. 59, which is a drop of six places compared to last year. Four universities have moved up the rankings; the University of Amsterdam, Utrecht University, Delft University of Technology and the University of Groningen.

The top ten consists exclusively of British and American universities. At the very top – for the seventh year in a row – is the British University of Oxford, followed by Harvard University in the US. Switzerland’s ETH Zurich takes eleventh place and the highest-ranked Chinese institution (Tsinghua University) occupies the sixteenth spot.

Danger

Rankings sometimes come in for criticism. The danger of rankings like these is that they encourage universities to narrow their focus to aspects that are likely to improve their score. In the past, some Dutch universities have even toyed with the idea of a merger, partly because pooling their resources would earn them a higher ranking.

The ranking criteria are not without controversy either. Internationalisation of staff and students, for example, is considered a plus, yet in the Netherlands there is also criticism of the unbridled influx of foreign students and the growing influence of English on education.

Furthermore, citations of scientific articles count for 30 percent of the score. This means that researchers are judged by articles that score well among their peers. The use of citation scores like these is now generating considerable resistance, with many arguing that research should be assessed along different lines.

Discussion