Trust in times of online education

Showing significant creativity and resilience, lecturers from all TU/e departments have rapidly embraced different techniques and tools to allow them to test the knowledge of the students in online exams while making sure that they are constantly being monitored from distance. Baring a few cases, students accepted this decision with little protest. But what are the implications and possible effects of asking our students to sit in front of a camera for a two-hour test? What message are we implicitly broadcasting to them?

Surveillance is not new to how students are assessed in universities. If the corona pandemic would not have occurred, students would still be asked to sit in big lecture rooms and work in silence while invigilators oversee that they work on their own. This is done to ensure that results of the exam represent the knowledge of students and not the result of crowd wisdom. But with the sudden switch to online education and online examination, and under the very strict social isolation conditions imposed by the government, ensuring that students do not cheat when taking an exam online from home has resulted in a rush to adopt far-reaching privacy breaching measures.

The fear that visual material (photos, videos) will find its way into the wrong hands and the cry not to breach privacy of students should not be taken lightly. But there is another, much bigger risk, to our education system, I fear. The risk is that we might lose the trust in/of our students when we come back to the university when the lock-down is over. One of the most exciting new ideas on the future of education, be it online or offline, is the idea of education built on trust and student ownership. But how much trust do we project if we use video surveillance?

Is using cameras and microphones the only way to ensure that no copying takes place? Would trusting our students (who are sitting alone at home) to solve the exam on their own, without being surveyed, pay out? Or would we see an enormous spike in exam grades indicating that, as students are on average equally smart year-on-year, they have been cheating in droves?

Initial results from exams taken with little or no video surveillance may give us a partial answer to the question. If we make the exam short in time and include enough questions in it, students will be mostly busy trying to answer to the best of their ability and may not be busy with trying to get answers from their fellow students (who are just as busy trying to solve the exams on time).

While I kept the cameras running as my students took their final online exam, I paid very little attention to what they were doing. The exam was randomized (different questions and different parameters) for every student, and with the time pressure they were mostly busy solving the exam. In the end the grades for the exam were nicely distributed. Many more students chose to participate in the exam (50% less students with a grade of 0) and the average grade of 5.7 (for the students who made a true attempt to solve the exam) was similar to the grade average in previous years.

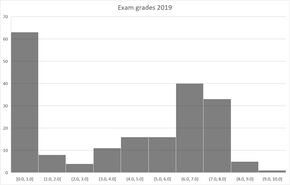

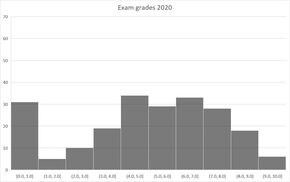

In another exam, which used no camera surveillance at all, the grades of students were also nicely distributed and showed great similarity to the grades in 2019. Some departments are openly debating the need for video surveillance and if the examples above can be used to encourage decision makers to make brave decisions, I will find that a very rewarding outcome.

In his book, ‘Humankind, a Hopeful History’ (‘De meeste mensen deugen’), Rutger Bregman suggests we should give people the benefit of the doubt more often. As he puts it in his book, what do we have to lose? Worst case our trust will be misused. Believing that people will choose for a negative behavior and acting upon these beliefs acts often as a self-fulfilling prophecy. If we choose to believe in our students, we may find ourselves surprised with the result.

I think, we should think carefully about how we test our students online. I am also convinced that if we spend more time creating more tools to verify and survey, the students will find ways to surpass and outsmart our surveillance solutions. In this arm’s race there are no winners only losers. Or maybe not, there are winners, the companies selling the surveillance software and tools, but the university, its educational staff and the students will all be losers.

![[Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/6/9/csm_BvOF_Oded_Raz_column_f4f4c489bd.jpg)

Discussion