Brainmatters | Phantom pain in Atlas

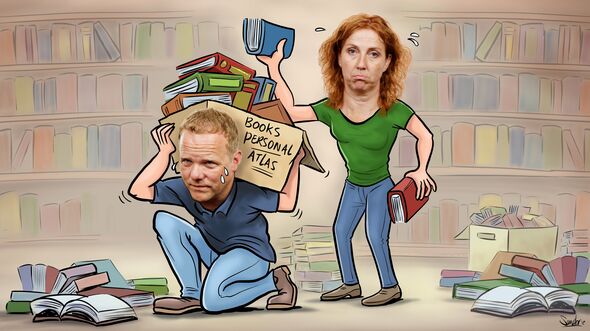

We are moving house. Admittedly, we have now changed our place of residence and have swapped our old home for something nicer, finer. But we are not yet feeling at home: our books are still boxed up in dark rooms and - worse still - in storage. That whole process is taking longer than planned and all this time we have empty hands and time and again we feel the want of that one particular book that just needs to be leafed through at that moment. We know where it stood, we know it's out there, but right now we just can't get to it.

Books are essential tools for thinking. Just as a carpenter can't do without a hammer, chisel and saw, a scientist can't do without books. A tool is not only an item that supports a skill - it is an integral part of that skill. As Einstein once said: “together my pen and I are smarter than I am”. Our tools for thinking ARE in a sense the thinking: they are inseparable from the creative and reflective process.

Digitalized books are easy to search through for keywords, author or year, but they are not books. They are not palpable, you cannot leaf through them, sniff them, feel their weight; you can't write notes in them or fold down the corners of their pages, lend them to someone or press leaves in them. They do not stand regally in the bookcase as palpable sources of thoughts, ideas, bodies of ideas, they don't spark a flash of inspiration or become a sudden aide memoire. They fall into oblivion. A book is part of your semantic network. It is an illusion that your body of ideas lives only in your head. It lives all around you, in your workplace, your notebook, the articles that you leave lying about, the books in your bookcase. This is the essence of the concept of extended cognition.

A paltry two shelves

As new occupants of Atlas we have been asked to make lists, of the books that we want to keep, the books we want to place in a communal open space, books that we are taking home, books that we'll give to a library, and books that we plan to throw away. On the understanding that one's personal bookshelf is no more than 1.5 meters long, and thus the number of books we keep is limited to about fifty; a paltry two shelves in a regular bookcase.

When something has been a fluent part of your thinking process, it cannot be removed from that process without pain. Just like someone who loses an arm will continue to feel sensations long after the moment of loss - known as phantom pain, sometimes very painful - as evidence of the intimate relationship that once existed with that arm, so it feels to be deprived of books that you have collected and carried with you all your life, that you have borrowed from or lent to colleagues throughout your student years and career.

Effrontery

The books in which we write are of inestimable value to our cultural and mental development; The art of printing is undoubtedly one of humanity's most important technological inventions. Books are not some dusty remnants of the old way of working, they are necessary tools for growth and innovation; they are the embodiment of flexibility in thought and action. That we, as scientists, should have to do without our books is an effrontery.

Yvonne de Kort | Professor of Environmental Psychology at Human-Technology Interaction

Wijnand IJsselsteijn | Professor of Cognition and Affect in Human-Technology Interaction

![[Translate to English:] Illustratie | Sandor Paulus](/fileadmin/_processed_/3/5/csm_TDO_cursor_16okt_2018_0a072ebcad.jpg)

Discussion