Why trains are not yet replacing planes

On medium distances, trains win in terms of speed and efficiency, so that is where the opportunities for sustainable travel lie

We often hear that train travel should replace flights. But is that feasible? General Manager of EAISI Carlo van de Weijer calculated that it is technically impossible to replace a significant portion of current flights with direct trains. Professor Oded Cats calls for a nuanced perspective in the polarized debate on sustainable travel.

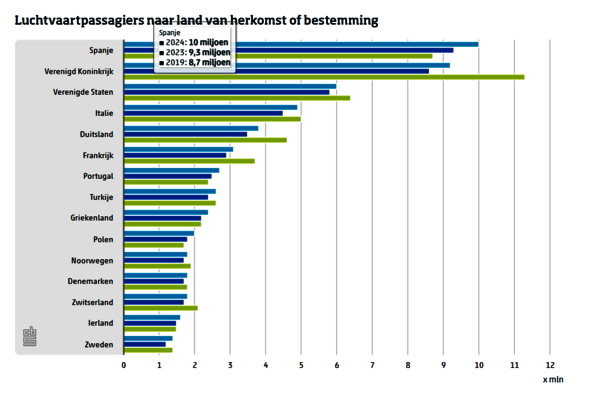

High-speed trains will unfortunately never be a serious alternative to planes, according to Carlo van de Weijer. “Amsterdam - Brussels, London or Paris is fine by train, I often do that myself. But if you look at replacing all flights with train travel in a profitable and efficient way, that would only apply to 2.5 to 5 percent of current flights.” Many scientists will disagree with him, but he doesn't mind: "We can cherish our differences and both work on solutions at the same time."

Oded Cats, professor of Passenger Transport Systems at TU Delft agrees that globally only a small share of the flights can be replaced by trains and even within Europe flights will also in the future remain the primary mode of travel for many connections. "For short distances, the car is often the mode of choice for many. In the midrange the train can on certain connections beat the car and the plane. In these middle areas of say 400-500km the train can be competitive. For this to happen it has be fast, reliable, well-priced and have frequent departures." These aspects all influence how competitive the train is and therefore how likely it is that people will choose the train as an alternative to the plane.

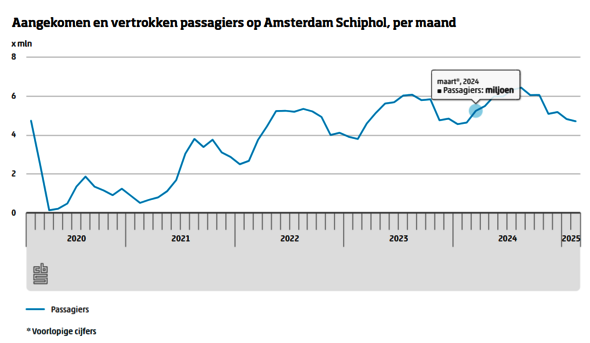

No decrease in air travel

Something interesting happened in Spain when a high-speed train was introduced on the Madrid-Barcelona route: the most busy route in the world in terms of number of flights. When the train was introduced, many people started using it, but air travel did not decrease. The total number of passengers on this route increased. More options brought more passengers. This could be a lesson to be learned for feasibility studies of future rail connections, along with other factors.

Professor Cats has conducted a lot of research into multimodal transport systems and tries to link these results to predict where future opportunities for the train will be. “We have created a map of the European network with optimal routes and frequencies. This is the outcome based on predicted travel demand within Europe, as well as how people make choices between the different transport options.”

In these middle areas of say 400-500km the train can be competitive. For this to happen it has be fast, reliable, well-priced and has frequent departures

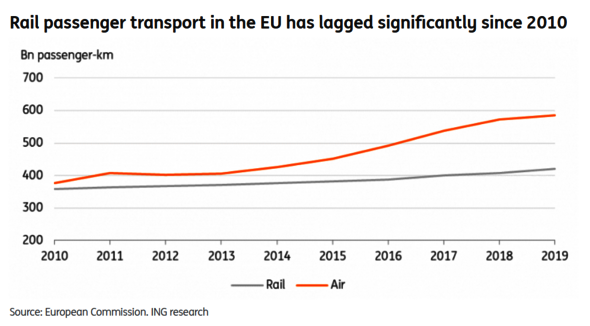

Constructing enough tracks for the train to become a real competitor to the plane does not physically fit into the landscape. Van de Weijer: “To replace just one third of European flights, you would need to add an estimated 20,000 to 30,000 kilometers of track. That costs a sextillion euros, an extreme amount of energy for all the concrete and iron, and it destroys our landscape.”

And what if people simply change trains more often to travel the same routes? “Well, that is possible, but it also causes more stress about possibly missing connections and takes longer in total. Moreover, due to the implicit vulnerability of the rail system, it is in the connections that things often go wrong in practice. Then fewer people will be willing to do it.”

Expectations too high

“I think that those who argue that trains will completely or largely replace flights set unrealistic expectations,” says Cats. “There is a lot we can gain with addressing the existing highly fragmented network in Europe. The goal of offering better train connections is not per-se to reduce flying, but rather to improve accessibility, connect places and improve travel opportunities."

For short distances, electric flying will become possible. For longer distances, we will fly on synthetic fuel

"Discussions focused on limiting air travel or blindly investing in rail connections without making sure that they are backed by a solid assessment are not conducive to improving transport. To make a train profitable, you need high volumes of passengers on the main corridors and create network effects by consolidating flows. This process is not very different from how airlines such as KLM developed their network over time.”

Future connections

The EU has drawn up a number of TEN-T corridors: routes where high demand for transport is expected in the (near) future. This could allow new railway lines to be constructed.

CO2 emissions

Van de Weijer firmly believes that CO2 emissions from air traffic must be reduced through technical solutions. “Passenger numbers will continue to increase, that is inevitable with the great economic growth in China and India. And if you then take one flight less, the impact on the whole is too small.”

The mobility specialist sees it as follows: “For short distances, electric flying will become possible. For longer distances, we will fly on synthetic fuel. For example, within the TU/e EIRES (Eindhoven Institute for Renewable Energy Systems, ed.) is working on that.”

Van de Weijer acknowledges our footprint due to our heavy flying in the Western world. “Of course, flying less helps to reduce its impact. Every kilometer that you fly less does not have to be compensated with technology. But it is simply not realistic to expect that the entire human race will fly less in the long term.”

Cats thinks it is especially important that while we can incentivize people to make certain choices for example by internalizing the environmental costs into the ticket costs, the traveler should ultimately always be able to make a free choice.

True pricing

Flying is currently still (much) cheaper than travelling by train. You always hear that this is because there is too little tax on plane tickets. “Yes, that is correct,” says Van de Weijer. “But even if you tax international travel fairly, which I am all for, travelling by plane is much cheaper than by train. Construction and maintenance of railways is very expensive and that makes travelling by train much more expensive than by plane. If you were to pass on all social costs, a train ticket within Europe would become 200 to 300 euros more expensive, while a plane ticket would cost tens of euros extra.”

Van de Weijer: “The train is seven times more environmentally friendly than the plane. Yet that same train produces more noise and damage to the landscape and therefore requires much more subsidy, which also counts as social costs. So is only CO2 reduction important, or the entire package of effects? You should not focus blindly on one consequence.”

In the Netherlands, the share of international passenger transport by bus is now even greater than by train

Cats also expects that including the environmental impact is likely to have a limited effect on prices and therefore the choices people make. It can however still tilt the balance for some services where airlines currently run a small margin. He stresses that when evaluating an investment, you should always look at the costs and benefits. “The costs assessment should also consider the impact on the landscape and the energy needed for production. For example, if the damage to the landscape and noise pollution are large, the extra costs of building a tunnel may be considered. To assess the benefits that will arise from new connections one needs transport supply and demand models to forecast the use of the future train services”.

International bus transport

Oded Cats also points out that it is important not to forget the role of international bus transport. “Since the arrival of Flixbus in the Netherlands, there has been much more supply and use of international bus transport. In the Netherlands, the share of international passenger transport by bus is now even greater than by train. Bus transport is flexible and has almost no infrastructure costs. Of course, it is slower than the train, but it is financially very competitive, which makes it extra interesting for certain target groups who have to watch their pennies.”

However, Cats also sees disadvantages of (international) bus transport. Transfers are not (yet) facilitated. “It is a point-to-point system, but it does offer many options.” Transfers are not yet possible everywhere: night trains do not offer them either, and neither do low-cost airlines such as Ryanair and Wizzair.

Banning versus stimulating

Where the ticket price mainly plays a role for the individual, for work trips there is more focus on the time the journey takes. A policy such as 'under six/eight/twelve hours you have to take the train if available' does not work according to Van de Weijer. "Yes, flying causes more climate damage than the train. But the train requires a lot more money, it is really more expensive than flying.”

“Even if you apply 'true pricing' to plane tickets. Then the train even becomes unaffordable. A train ticket only covers 16 percent of the actual costs. A plane ticket within Europe between 60 and 70% of the actual costs, and with the new flight tax that creeps up to 100%."

Cats argues that almost all transport investments – including roads and rails - involve governmental investments “We choose to finance (public) transport considerably because it generates benefits for society. We should do so also in international travel whenever it makes sense.”

Behavioural change

The professor from TU Delft does try to bring about a change in travel behavior within his department. “We know from research, even based on travel attitudes and behavior of academics that good will is not enough for a behavioural change to take place. “We tell our colleagues: travel consciously and take the train when possible. But of course there are exceptions, for example if you have family or work commitments which prevent you from travelling by train on the next day. We stimulate through rewards, such as allowing people to book first class if they travel by train.” Incidentally, the latter is also the case for business trips within TU/e.

Cats does not try to impose anything in his department, but expresses the expectation that people will not travel more than 12,000 kilometers per year by plane. "Then people take the destination into account in their choices and/or consciously travel less one year so that they can travel a bit further the next year.”

Van de Weijer indicates that you need a lot more track to be able to replace all flight connections one-on-one. “You can go from A to B with one flight or via one railway line. But if you want to connect A with B and C, you already need three tracks. For five destinations, you need a total of ten tracks. This increases quadratically. Connecting 50 cities means that you need 1225 railway lines for direct traffic. Or fifty airports.” He explains this in this fragment of an explainer video about the possibilities of the train as a replacement for the plane:

But are there no other solutions? Van de Weijer admits that there is some room for combining with certain destinations and the railway lines involved, but that still results in around 1000 railway lines. Construction and maintenance of 50 airports is much cheaper and more sustainable than that of 1000 railway lines", says Van de Weijer.

Cats strongly disagrees. “This is simply not how passenger transport works. First of all, you need much fewer tracks and lines for two reasons. To connect any number of cities the number of connections strictly needed is no more than the number of cities minus 1 (for example, we can connect 4 cities using 3 connections, either with one hub and three spokes or by connecting those using a single line). This is most cost efficient but may compromise service quality (speed, comfort, reliability).”

Connections

“The other extreme is connecting each pair of cities directly to each other. This is massively expensive and unnecessary. In reality, we know from metropolitan public transport networks that the most cost effective solution includes about 30% of the connections, with those being sufficient to connect all cities using a compact network. We can expect this to be even lower in long-distance travel.”

“Second, like in aviation, network effects mean that there are more and better opportunities to transfer. For example, in our study on service design for Europe we connect 116 cities using between 50 and 100 lines. This is two orders of magnitude lower than the approximately 6500 lines which the quadratic argument implies.”

Carlo van de Weijer has a background in mechanical engineering and is a mobility expert. He carries a broad experience in the automotive industry with among others Siemens and TomTom. Currently he is managing director of the newly founded Eindhoven Articial Intelligence System Institute (EAISI) at Eindhoven University of Technology.

Oded Cats is a professor and head of the Department of Transport & Planning, part of the Civil Engineering and Geosciences Faculty at TU Delft. He is also co-leader of the Smart Public Transport Lab. He has been awarded with a ERC personal grant called 3MARS devoted to the dynamics of long-distance passenger transport systems.

Discussion