Mayday. “There’s someone in our network that we don't know."

A reconstruction of the cyberattack through the eyes of the IT staff

While most staff and students are soundly asleep, Joost de Jong, Michiel van Grootel, and Martin de Vries of LIS are on the edge of their seats. Saturday evening, January 11, 2025, they receive a notification that a hacking operation is taking place in TU/e’s systems. The trio immediately launch a counterattack. A reconstruction through the eyes of the IT staff.

9:20 PM. Security operations manager Joost de Jong is at a friend’s place watching soccer, PSV against AZ. Somewhere else in the world, someone has started a hacking operation against TU/e. Something that no one except Product Owner Michiel van Grootel suspects yet. Van Grootel is off and watching some stuff on YouTube, his phone nearby. When he’s not on the clock, he does almost always read the email that arrives on his business account.

Van Grootel deals with the university’s critical digital infrastructure. That evening, an email arrives from the ‘security tooling’ – tools to monitor the university’s digital security – showing unusual activity in the network. He calls an engineer from his Compute and Storage Services team to verify the matter. “It doesn’t take long for us to draw the conclusion that we need to escalate,” he says.

9:35 PM. Security Operations manager Joost de Jong is at a friend’s place watching soccer and gets a call from one of his team members who has on-call duty and was the first to be notified when the issue was escalated. Quickly realizing it’s serious, he cycles home and grabs his laptop.

It feels like the Titanic has a breach in its hull affecting so many compartments that it can’t stay afloat

10:13 PM. Chief Information Security Officer (CISO) Martin de Vries receives a message about the hack in the LIS crisis chat, but doesn’t immediately notice it on his night off. Enjoying a documentary about Sylvester Stallone a short while later, he glances at his work phone. ‘We have a serious problem,’ he reads. From his couch, he can’t do a whole lot and waits for an update, which arrives about ten minutes later.

High privileges

11:15 PM. Not much later, seven people are in a Teams meeting: “There’s someone in our network and we don’t know who.” More and more points of access pop up: the intruder is spreading rapidly. “They now possess an ‘admin’ account with such high privileges that it feels like the Titanic has a breach in its hull affecting so many compartments that it can’t stay afloat if no action is taken. This account really can do anything,” De Jong confirms.

During the online consultation, he sees that the hacker is making attempts to install things. De Jong feels a chill run down his spine. “An admin account connecting to everything, a spider web that keeps growing. And with every account we close, another one is created as a replacement.”

Every day, De Jong and his colleagues receive 11,000 reports of anomalous patterns. De Jong checks the data and assesses whether further investigation is needed. With 27,000 people in the network, something happens every day. Due to security automations, many reports no longer need to be responded to manually, but January 11 was an exception in that regard.

11:15 PM. Everyone agrees: all connections to the network must be severed. De Jong notifies his colleagues from the network team, who are momentarily taken aback. After all, this kind of thing never happens. And it may well have consequences for users of research setups or student teams, for example. But doing nothing will have even greater consequences. “The network must be shut down now,” is the decision. Mayday.

Shutting down the network

That means the university can’t ‘open’ on Monday. This won’t be a simple reboot. Shutting down the network also means that the IT officers themselves will have nowhere to go. De Jong is prepared for that. “I have a hard-copy list with important phone numbers for emergency situations,” he says. This is such a situation. But even though he can reach people, he won’t be able to access the security tools or recovery procedures that are on the network.

In the online meeting, they agree to all come to campus, because Teams won’t work anymore once they shut down the network.

Midnight. Martin de Vries gets in his car to head to campus. While driving, he calls the police to report the hack. It’s not every day that their control room receives such a report. “Sorry, you have a what to report?”, he is told. “But in the end it was handled well.”

As he’s driving, several thoughts go through De Vries’s head. ‘Our time has come to deal with a hack. What am I going to find when I get there? Seeing something for yourself is different from hearing about it on the phone,’ he thinks to himself.

12:30 AM. Arriving at the campus, De Jong sees police officers, called in by De Vries.

When he arrives at the Atlas building, the Chief Security Information Officer presses the intercom. Someone from security – present 24 hours a day – lets him in. He walks into a totally empty and dark building and takes the elevator to the 12th floor.

The seven men gather with a case of Coke Zero and a few cans of Red Bull that Michiel van Grootel loaded into his car before he left. It’s going to help them stay sharp in the long night ahead.

1 AM. The network is shut down and no one can do or see anything anymore. De Jong: “You think that this way you also stop the hacker, but still you have that little voice in your head saying, ‘What if he’s still in, using an unknown server or a 4G dongle (a device that allows you to connect to the Internet via a mobile network, ed.)?’”

Catch their breaths

The team can now catch their breaths and come up with a plan of action. After all, when the network is reopened, the hacker will also be able to continue. “It’s like feeling around in the fog,” De Jong says. Then, with a serious look on his face: “IT people are quite fond of discussing things at length, but now there’s a silent focus and joint resolve to get things done. This person has to be stopped.”

With the network down, everyone has a bit more peace of mind than before. It’s likely that the hacker can’t continue what they were doing. But as soon as you open something up again, you have to watch out. Everything has to be done in a controlled and careful manner.

3 AM. Out the window, De Jong sees the people from security company Fox-IT arriving. They are coming for the forensic work: how did this hacker get in? The team gets to work, but for the TU/e staff the first concern is to keep the hacker out of the network.

5:15 AM. De Vries drives his car home to get just under an hour of sleep. At 8 AM he’s back on campus.

8 AM. This Sunday morning, the central crisis team is also present. Further discussion is taking place on what next steps to take and how to inform the community about the situation.

The days after

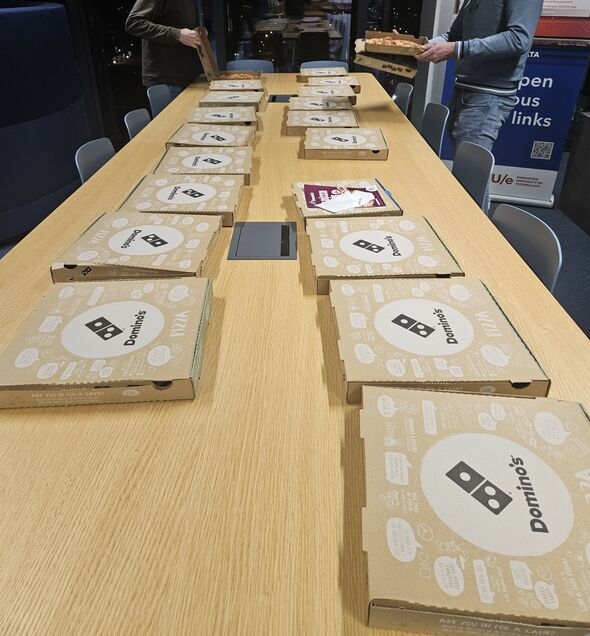

In the days that follow, the 12th floor of Atlas remains the domain of IT experts helping to get the network safely back up and running. The university provides the necessary energy in the form of meals to support colleagues.

When you’re hovering over a warming bowl of lasagna, there’s also some room for lighthearted humor: isn’t this just one of your pranks, Piet?

De Jong: “When you’re hovering over a warming bowl of lasagna, there’s also some room for lighthearted humor: isn’t this just one of your pranks, Piet?” But who was behind the cyberattack remains unclear. As the person or persons were caught so quickly and the network was shut down, hardly any usable traces were left behind.

Still, the perpetrator or perpetrators had been inside several days before the hack, De Vries says. “And then they picked this moment on Saturday night for a large-scale attack.”

The university harbors an inherent contradiction that’s tricky for security: scientists want as much openness of research and data sharing as possible, but from a security perspective you want as much closedness and control as possible. De Jong used to work for the Ministry of Defense. There, you have the other extreme: there’s a fence around the compound, every door is locked, and there is armed surveillance. “Security works best if you can arrange procedures optimally. But people want something different all the time, especially in a dynamic science environment. That’s tricky.”

Critical half-hour

Van Grootel is the man who ensured that TU/e gained at least half an hour compared to the automatic response that’s activated 24/7 in case of anomalies found by the security tools. A half-hour gain is a lot in this crisis situation, says De Vries. “With an extra half hour, the attackers would have been much further along in doing damage and encrypting all the data. The moment we launched the counterattack, they had to respond to our defensive actions,” he reflects after shutting down the network.

You shouldn’t forget what’s important in life by getting caught up too much in the events of the day.

The IT officer was only home for a short time over the weekend. “I’m quite experienced in these things, but you see that with some colleagues the tension becomes too much at a certain point. Then you send someone home for their own good. People have put in such fantastic effort, that touches me.”

Van Grootel himself decided to go home briefly on Sunday for a power nap and to give his little daughter a hug. “You shouldn’t forget what’s important in life by getting caught up too much in the events of the day. And recharging is also essential to be able to be meaningful again at work.”

Lessons learned

Looking back, Van Grootel and his colleagues also learned new things from this crisis. “For example, we need to compartmentalize the security tooling better. Then we can more easily shut something down, but still access useful security tools ourselves to monitor hacking activity.”

Still, according to the trio, things went relatively well and a lot of damage was prevented. “Compared to a few years ago, we were now much better prepared for a hacker. And the whole thing hasn’t only taught us what can be improved in terms of technology, but also in terms of communication to the outside world. It’s a complex environment, a university. Everyone needs and wants to be able to do everything in order to do good research. And that comes with risks. Incidents like these shift the balance of what can and cannot be done. There’s more standard blocking now than before.”

Chief Information Security Officer (CISO) Martin de Vries has been nominated as CISO of the Year, in part for his handling of the hack at TU/e. Together with Vladimir Cibic of KPN and Florence Mottay of Zalando he’s competing for the distinction. The results will be announced on May 27.

Discussion