Home Stretch | A smooth flow onto the train

TU/e researcher Cas Pouw applies physics to the flow of train station crowds

Making a last-minute sprint to catch your train? That can be a real challenge during rush hour. TU/e researcher Cas Pouw studied crowds at the train station and used fluid dynamics theories to create a predictive model. And he has tips on how to board a train quickly.

As a frequent train traveler, Cas Pouw is all too familiar with zigzagging his way through the station. “You’re trying to catch that one train in the morning, but then it turns out half the crowd at the station is trying to do the same thing.” But there is a difference between busy and busy, Pouw emphasizes. When does it actually lead to unsafe situations? And how accurately can you predict how people behave in a train station? “It’s a complex issue.”

Psychologists have long studied the way people move in groups, but Pouw approached the topic through a physics and mathematics lens to describe crowds and identify patterns. After four years of “tracking little figures” – in close collaboration with railway operator ProRail – he now has a first successful predictive model, including a new sensor technology for capturing people’s profiles in 3D. On Wednesday, he will defend his dissertation at the Department of Applied Physics and Science Education.

Fluid flow

So how does one view rushing crowds through the eyes of a physicist? Pouw laughs. “Just look at a moving crowd from above. It’s essentially a flow. And that’s how we came up with the idea of applying fluid dynamics theories.”

Pouw explains that you can model fluids at different scales. “You can map the behavior of individual molecules, but also describe how the density of the fluid flow itself changes over time. We can apply that same concept to people. How do individual people move? And then if we zoom out, we can observe how a crowd – which is itself a part of a larger whole – changes. If you zoom out even further, you’re looking systemically at movement within a network. For example, how train travelers move through large stations across the Netherlands.”

And so, Pouw set out to investigate whether and how people fit into a fluid model. He wanted to build a model that was as generic as possible, “without too many bells and whistles, so that it could be applied in as many situations as possible.” But a model is nothing without data, so the first step was gathering it. However, there were a few bumps along the way.

Level differences

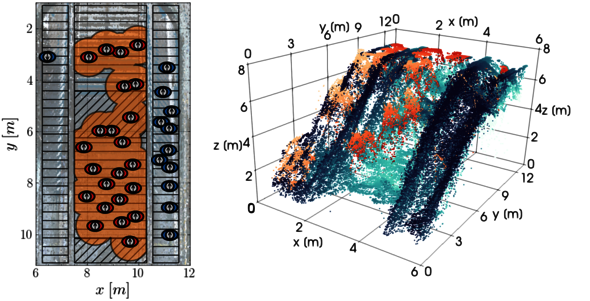

“Privacy is crucial; we should not be able to recognize individual people in any of our measurements. That’s why we use depth imaging, where we monitor people from above as silhouettes.” To be able to track those same people over a longer trajectory, Pouw and his colleagues developed new sensors. These sensors were tested thoroughly in various studies conducted in Metaforum’s market hall. The staircases and escalators at the station posed an additional challenge, according to Pouw. “If you want to cover a large area, you need multiple sensors. You can stitch their images together afterward and if necessary, correct for differences in perspective. But making corrections is really tricky if the surface isn’t flat. And a train station inevitably has lots of level differences, with people moving in opposite flow patterns on top of that.”

Using optimized sensor technology, Pouw was eventually able to collect data at Eindhoven station for a whole year, he says with some pride. “We’re one of the first research groups worldwide to be able to characterize people’s behavior in a real-world setting over an extended period – without interfering. Being able to make such accurate measurements in public spaces is still very new.”

Bin in the way

And the great thing is – as demonstrated by this enormous pile of data – that train travelers map remarkably well onto a fluid dynamics model. Station designers can now start using the model Pouw developed to improve the safety, efficiency and comfort of train travelers.

“We’ve observed that as the station gets more crowded, people’s individual walking speeds tend to converge. Something of a crystal structure forms, where people have certain positions relative to one another and maintain them. That also affects how a staircase is used, for instance. And how certain objects can become obstacles to the flow of people when it’s crowded. Like the trash bin at the Kiosk that people try to squeeze past during rush hour. Simply moving such an object can already have a positive effect on the flow, and we’re now able to predict that very realistically.”

Boarding process

In addition, it is now possible to monitor how large crowds can be better distributed across the station or platform. “We’re going to use this tool to study the effects of crowd management measures. For example, how well travelers follow projected directions, and which symbol or color works best.”

And as he has often noticed himself at stations, “it can be useful not to always follow the crowd; the shortest route isn’t always the fastest. It could just make the few seconds’ difference you need to catch your train.” Pouw has one last tip for getting on the train just a little faster. “We also looked at the boarding process – a very culture-specific public transport phenomenon. On Dutch platforms, two groups usually form on either side of the train door. We’ve observed that during rush hour, the passageway is almost always too narrow for an efficient flow. That slows down the entire process, so there’s definitely room for improvement there. We see that the people who are closest to the door itself, so up against the train, tend to board first.”

PhD in the picture

What is that on the cover of your dissertation?

"After submitting my final manuscript, I spent ten weeks traveling around South America. At the Iguaçu Falls on the border of Brazil and Argentina, I suddenly saw my research captured in a single view: long lines of moving people and swirling fluid flows. Calm in some places, more turbulent in others. It was very cool.”

You’re at a birthday party. How do you explain your research in one sentence?

“I do research on how people move in very large groups.”

How do you blow off steam outside of your research?

“A lot of sports – swimming, cycling, bouldering. I try to keep a healthy balance between work and relaxation. Speeding up when needed, but also slowing down sometimes. Festina lente – make haste slowly – is the motto my parents gave me at birth. I’ve really come to live by that.”

What tip would you have liked to receive as a beginning PhD candidate?

“Be curious and make sure you have a strong intrinsic motivation; it will help you when things get tough.”

What is your next chapter?

“This year, I’ll still be working as a postdoc in my research group, and one day a week at ProRail. So nothing new in that sense. But in the meantime, I’m exploring how I could start my own business. To see how I can help companies address crowd-related challenges, which are increasingly becoming societal issues.”

Discussion