Professor Bert Meijer (70) not yet ready to be emeritus

The chemist first hopes to unravel the secret of homochirality

Although university professor Bert Meijer is well past retirement age, he still holds his position in the Ceres building. And he intends to stay there for the foreseeable future. Why has TU/e extended his appointment? And what goals does Meijer wish to achieve before he leaves the university?

In principle, a TU/e employee's contract ends when they reach retirement age. Sometimes, the university deviates from this rule if there is a significant organizational interest. This might be the case with the appointment of professor Bert Meijer (70).

Meijer is internationally renowned in his field. His group conducts fundamental research on polymers as well as research focused on applications in sustainability, medicine, and electronics with its supramolecular systems and materials.

The research lies at the intersection of chemistry and biomedical engineering. Meijer is therefore active in two departments: Chemical Engineering & Chemistry and Biomedical Engineering. He plans to continue this work for another 2.5 to 3 years. In any case, he wants to have retired by the age of 75.

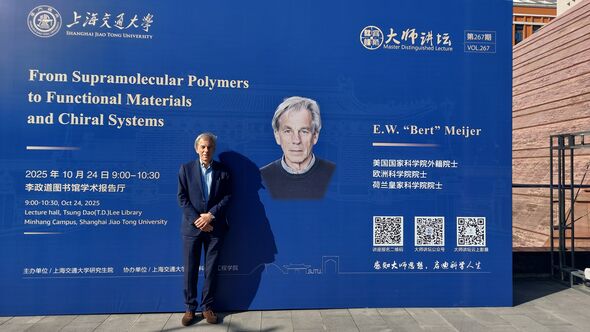

When Cursor spoke with him, Meijer had just returned from China, where he was impressed "by the appreciation you receive as a professor there: my arrival was announced on a huge billboard outside, I was driven around in a chauffeur-driven car, and I was offered several contracts." The fact that Meijer is already 70 didn't bother the Chinese.

He has, however, declined the offers; "My wife doesn't want to leave here, I enjoy Eindhoven, and I don't like the food in China," he says waggishly.

Start-ups

Meijer has currently been working at TU/e for 34 years and has already built a considerable legacy. He looks proud. “Our field may not be very 'Brainport-like,' but that's not a problem. We can make a big impact, and we have already done so.”

“I started in 1991 and, together with René Janssen, established SMO, a research group for macromolecular and organic chemistry.” They started with ten people and now have four hundred employees, spread across more than ten research groups in three departments. The Institute for Complex Molecular Systems (ICMS), which he founded, has spawned more than twenty start-ups.

International recognition for his work is evident, for example, in the awarding of an honorary doctorate by the University of Copenhagen on November 14. Meijer receives the honorary title for his ‘pioneering work in organic and polymer chemistry and collaboration with the University of Copenhagen,’ according to a press release from the Danish university.

Succession

With his dual background in organic chemistry and polymers and long track record, finding a successor is certainly difficult. “There will be no successor for me," Meijer reveals. However, he doesn't see that as a problem. "The cluster of excellent molecular chemists can easily continue without me.” The professor is pleased with what he has been able to accomplish for TU/e and the academic community. What not everyone knows is that in addition to research, he also provides policy advice, for example to the Ministry of Education, Culture and Science. Meijer was instrumental in developing the sector plans for science. "I think my strength lies in being a good listener, operating within the framework, and never doing anything out of self-interest."

Staying on after retirement age is not a right

The Collective Labor Agreement for Dutch Universities stipulates that an employee's contract ends when they reach the state pension age (AOW). Continuing to work after retirement is an option, but not a right.

Continuing to work after retirement is only permitted if there is a demonstrable organizational need for this. For example, if the employee has unique competencies that are difficult to find due to a tight labor market. The employer's needs are paramount, not the employee's.

Meijer is still employed for two days a week. However, he claims to be on campus five days a week because his work is also his hobby. The question of why Meijer was allowed to remain employed was submitted to TU/e, but remained unanswered. It could be related to his reputation in the field and the benefits this brings to the university.

Organizational Interest

‘Unequal treatment of employees, by offering a new employment contract to one employee of state pension age and not to another for unclear reasons, must be prevented,’ according to the TU/e pension policy (intranet). How does the university prevent this? "That's precisely what we do with this policy," says spokesperson Ivo Jongsma. He is referring to the passage that states that, in principle, there will be no contract extensions unless there is a compelling organizational interest.

"For the group of employees for whom this is particularly likely (professors, associate professors, deans, or directors of operations), this interest must be clearly stated in a proposal from the department to the Executive Board, and the Executive Board decides. For other positions, the assessment (based on the same criteria) will be carried out by the department board."

Bucket list

Meijer still has several plans for the coming years in his working life. He wants to travel less, although he has said so in recent years as well. His wife regularly reminds him of this intention. Still, the professor has one more trip on his bucket list: visiting Antarctica. But his wife isn't keen on a South Pole vacation, and neither are his friends. Traveling there by himself is becoming more and more of an option for Meijer.

He muses on how quickly time actually flies and reflects on the transience of life. "I'm seventy and have already lost quite a few friends, at a relatively young age. If I live to be eighty, it means I have only ten summers left. That's not that many, and that realization is suddenly kicking in more than ever before."

Homochirality

Besides that trip to the southernmost point on earth, Meijer also has a scientific challenge on his bucket list. He wants to research "the origin of homochirality in space and time."

Chirality means that an object or molecule doesn't coincide with its mirror image, just as your hands don't fit together perfectly. Chiral molecules exist in two forms that are each other's mirror images (enantiomers), but they are not identical. It was once determined during our lifetime that only one of the two species survives. All molecules in our bodies therefore have one type of chirality: they are homochiral. So sugars and amino acids, for example, have their specific shapes; but DNA and collagen also only exist in one chiral form.

Homochirality plays a role in many dimensions and is formed over time. Meijer wants to know the physical background that determined this and what unknown consequences it has. "There's still so much we don't understand, much more than what we do understand. I don't know if I manage to solve this major scientific question before I retire, but I hope so."

Meijer notes that he looks back more and is impressed by the development of science since he began. "Knowledge and expertise have exploded during my lifetime. In my birth year 1955 you could share all existing knowledge about DNA in a two hour lecture; now this will take many years."

Given the vast amount of activity in science, Meijer believes universities need to make more discerning choices. Dare to specialize, is his message. "That also attracts new talent, which leads to more funding and better research opportunities. My sector plan concept is based on choosing." He envisions a bright future for TU/e: "an MIT on the Dommel."

Discussion