Skipping class, but not work

Students are spending less time on their studies

More and more students are working alongside their studies, and as a result, they are dedicating less time to their coursework. For many, it’s not just about income, but also about gaining practical experience: “It’s just fun to work in different environments.”

Rover is in his final year of the university bachelor’s program in Humanistics and works twenty hours a week alongside his studies. “I work behind the bar at a music venue. It’s really enjoyable because you meet a lot of people, but the night shifts are exhausting.” He admits that his studies sometimes suffer as a result.

He is not alone. Statistics from CBS show that 62 percent of all bachelor students at universities and universities of applied sciences earn income from a part-time job.

More people are concerned because part-time work can come at the expense of studying. There are also signs that students are attending fewer classes. How can this trend be reversed?

Fewer hours spent studying

Many university students have a part-time job, but often work only limited hours: 60 percent work a maximum of twelve hours per week. In the bachelor phase, few students work full-time. However, in the master’s phase, 18 percent combine their studies with a full-time job. Apparently, they work on their thesis during evenings and weekends.

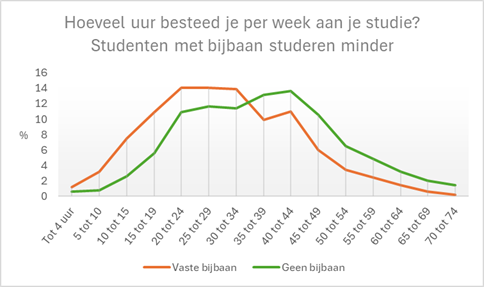

That working affects studying is confirmed by the annual Studentenmonitor. Students with a fixed part-time job spend less time on their studies.

On top of that, students report that they are generally spending less time on their studies than before. This trend has been visible for years. In higher education around 2018, just over 60 percent of students spent more than thirty hours per week on their studies. Recent figures show that percentage has dropped slightly.

Study credits

This is notable because a university program is theoretically based on full-time engagement of forty hours per week, which is also the basis for the credit system.

Yet universities often suggest that part-time work can be balanced with studies. For example, the University of Twente states, “You don’t have to choose. You can study and work.” Tilburg University actively directs students to job portals, and Utrecht University has its own vacancy bank. At TU/e, Euflex, a fully owned subsidiary of the university, helps organize student part-time jobs and other flexible positions.

Having a part-time job has become so common that students now expect flexibility from their programs. For Rover, combining work and studies is fairly manageable: he has classes on only two days per week. In addition to his work at the music venue, he is active in the University Council, which takes up roughly a day each week.

Mandatory attendance

With so many students working and spending less time on their studies, one thing is clear: students sometimes skip lectures or tutorials, especially if attendance is not compulsory.

Almost everyone in higher education has probably heard stories about half-empty lecture halls, but hard data is scarce. Attendance is rarely tracked, at least not centrally.

Researcher Rick Ikkersheim (Hogeschool Inholland), who specializes in study success, calls the lack of hard data a blind spot: “Increasing attendance is the quickest route to reducing student dropout. But if you want to address it, you first need to know the current attendance levels.”

Absent students are often labeled as unmotivated, Ikkersheim hears when discussing this topic. But he believes you cannot simply place the blame on students. You have to understand what is really going on.

Software solutions

There is renewed attention on mandatory attendance. Some universities, such as Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam and Leiden University, require first-year law students to attend tutorials and monitor attendance using special software.

Miss too many sessions? The consequences can be severe; in extreme cases, students may be barred from taking exams. And this is intentional, according to the “attendance team” at Vrije Universiteit: “Missing first-year law tutorials now affects their study progress. They cannot make up for it with an alternative assignment.”

Do these students then struggle to combine mandatory lessons with part-time work? According to Vrije Universiteit, if students are serious about obtaining their degree, they will attend required classes, even if it means working fewer hours.

Adults

Sarah Evink, chair of the Interstedelijk Studenten Overleg (ISO), finds such measures difficult: “Students are adults and can usually tell when they really need to be present. And if things go wrong, they can learn from it.”

At the same time, she does not want to dismiss mandatory attendance entirely. “I think a tailored approach is important, and decisions about attendance should be made close to the program level.”

Income is essential

Researchers note that students who attend lessons regularly are less likely to drop out. The cause is unclear—it could be that these students simply put in more effort and would have succeeded anyway. For students, classes do not always feel crucial.

Rover needs the income to pay his high rent. But besides money, his work for the University Council and the music venue gives him valuable experience, allowing him to develop various professional skills. “It’s just fun to work in different environments.”

According to him, part-time work should not be necessary for basic expenses—but currently, it is. According to Nibud, studying costs nearly €1,200 per month (rent, groceries, tuition, etc.), while the basic student grant for students living independently is only €324.

An HBO student earns an average of €833 per month through work and/or internships; a university student earns around €690. Nearly four in ten students do not have a part-time job; the question is how they manage financially.

Parents

ISO chair Evink explains: “Some students are lucky to receive significant support from their parents. Others simply cannot have a part-time job, like medical students. They may literally be gone from 7 a.m. to 7 p.m. for their clinical rotations, accumulating high student debt.”

Of course, many students also reduce costs by choosing to live at home.

Ultimately, 57 percent of students report that they can make ends meet comfortably (Nibud, 2024), but a significant portion struggles. Student organization ISO therefore advocates increasing the basic student grant to €530.

Happy employers

Should we simply accept that students will work alongside their studies and spend less time on coursework? Employers probably won’t mind. They benefit from students as an inexpensive, flexible workforce in a tight labor market. Many students also work irregular hours.

Rover prefers fixed workdays, he says, but sometimes runs into scheduling conflicts due to his variable class timetable. He would like to have set days off each week.

Ikkersheim understands this. Programs must first provide a solid structure, he says. Most students need regularity in both their studies and private lives. “In practice, I think many students treat their studies part-time. If we don’t make education mandatory, they choose activities that carry a sense of obligation, like work, sports, or social commitments.”

According to Ikkersheim, there is only one solution: attendance must become the norm again. A cultural shift is needed. He advocates a “mutual obligation”: students must attend classes, especially in the first year, in exchange for engaged lecturers and an attractive schedule that allows part-time work without compromising student commitment.

Dropout and study success remain stable

That students are working more and studying less does not immediately affect their chances of obtaining a degree. It does not lead to higher dropout rates. In the first year of university, average dropout is 5 to 7 percent.

However, study success is already not very high. Many students experience delays. Only 64 percent of university students complete a three-year bachelor within four years. For technical programs, this percentage is even lower: only half earn their degree within four years.

Student organization ISO advocates for students. They believe delayed graduation has gained too negative a connotation. What defines success? According to ISO chair Evink, the pace of study matters less as long as students cross the finish line. “When you ask students what they consider a successful study, the most common answer is ‘earning a degree,’ and the least common answer is ‘graduating on time.’ Students prioritize personal development.”

But if delays are due to insufficient income, it’s a different story. Evink worries about the many students with large part-time jobs: “Many students work more than sixteen hours a week. That comes at the expense of their mental health.”

Discussion