Business or pleasure

In many ways, the allure of Europe is its internal proximity. The visa-free travel across the Schengen region is a key attraction for tourists and students alike, and makes much of European science and business possible. It is so ingrained here, especially in recent generations, that the concept of travel restrictions is almost otherworldly.

I remember having a similar conversation several times in the last few years where friends were at times surprised, almost shocked, that they needed a visa to visit India. The reaction was often almost a “how dare you?”, a symptom of some odd entitlement as if bestowed by divine providence. However, reality couldn’t be further from this utopian dream.

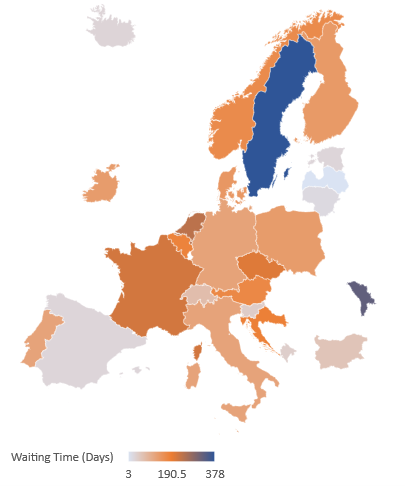

I had been planning to attend a conference in the United States in June this year, as a sort of a wrap-up for the PhD, to present some of my research, advertise the lab, and to cast a net among potential employers. Coming from India, whose passport allows visa-relaxed travel to just a handful of nations, I was very much aware of the need to apply for one. But a quick search was enough to paint the picture (see map); across all American embassies and consulates (> 30) within the Schengen area, there were hardly any that had any appointments available within a few weeks. And even the ones that did (Spain, Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia, Slovenia), only catered to local residents.

For instance, one had to wait over 240 days to even cross the gates at the consulate in Amsterdam. (Mind you, my average European reader, I do not refer to the ESTA which requires you to pay pocket change and fill out a short online form in order to get your travel authorization.) My hopes were therefore pinned to the only exception, Switzerland, where I booked my spot. But a couple of weeks later, they too flipped, deciding to serve only residents of Switzerland and Liechtenstein, effectively crushing my plan with a blunt shrug.

In that moment, it may have been infuriating since the arbitrary luck of being born in a tiny part of the world effectively elevated one’s status over others; only citizens from about 40 countries qualify for a visa waiver when travelling to the United States, for instance. It effectively implies that a small section of the research community has grossly unequal access to an audience, which invariably contrasts the egalitarian values that science supposedly espouses.

Some of such differences are explicit elements of being beyond one’s country. As a student, for instance, one has to guarantee a certain ECTS per semester or expect an unfriendly call from the immigration department. As an employed researcher, the license to stay somewhere is tied to the employment contract; as a result of that, there’s often a scramble to figure out the next gig, not only because it affects one’s income, but the very opportunity to be somewhere. However, as this incident shows, there are silent inequities that aren’t definite parts of the deal and only appear as circumstance, even though they are clearly policy. The soapbox must belong to all of us. For now, it doesn’t.

Discussie