Home Stretch | Many shades of gray

From pencil ink to personal resilience: the PhD journey of chemist Laura van Hazendonk

We know graphite as the core of a pencil, ranging from light anthracite to deep black. Tiny particles of it can now be used as a new, more sustainable ink for printing electronics. TU/e researcher and former Provincial Council member Laura van Hazendonk will defend her dissertation on Thursday, October 2.

At first glance, a dissertation doesn’t reveal the story behind its creation. Every PhD journey comes with ups and downs. Sometimes, though, the downs are deeper than one could imagine. In such cases, completing a PhD project is no longer something to be taken for granted.

In that light, the cover of Laura van Hazendonk's dissertation takes on a whole new meaning. Her son Ties is inseparable from her memories of writing—the growing belly behind her laptop—yet everything changed when he passed away from a bacterial infection just a few weeks after birth. “At that point, nothing matters anymore, certainly not a little book like that.”

Still, she now holds her dissertation in her hands, after a dark period. “My father paints a lot, usually in bright colors. But when I saw this work of his, with all those shades of gray, I knew immediately it had to be my cover.” Van Hazendonk leans forward in her chair. She speaks openly about her grief but insists—driven researcher that she is—that her scientific work should remain the focus here. She pulls out a pencil.

Ink from a pencil

“Did you know that every time you write with this, you’re actually creating graphene nanoparticles? With new technology, we’re trying to turn such ‘pencil particles’ into ink for printing electronics.” And that’s urgently needed, Van Hazendonk stresses, because the electronics industry is highly polluting—especially the etching process, she explains. “Most electronics are made by etching. Put simply, you take a sheet of metal and dissolve everything you don’t need with strong chemicals. That creates a large waste stream, often full of toxic substances.”

Printing, by contrast, is often a more sustainable option. “You reverse the process and only deposit material where it’s needed. We’re trying to develop a ‘low-threshold’ printing ink. Right now, a lot of silver and copper are used in making electronic components. Their electrical and thermal conductivity is excellent, ensuring fast and precise signal transfer. But the downside is becoming increasingly clear: mining them harms water and soil quality. They’re also scarce, expensive, and harmful to human skin, which makes them impractical for e-textiles, fabrics with sensor functions.”

Wonder material

The CE&C Physical Chemistry group has long been researching how the electronics industry can become more sustainable without losing key properties like conductivity. Van Hazendonk focused specifically on printing ink and the use of graphene, a relatively new “wonder material” with unique properties. Producing graphene—a single layer of carbon atoms arranged in a distinctive structure—remains challenging, especially on an industrial scale.

The alternative method Van Hazendonk developed to make graphene ink is more sustainable. But she immediately adds a note of caution: “We should remain critical of applications, especially in our consumer society. It shouldn’t be a license to start producing all sorts of cheap electronic products we don’t actually need.”

Gray streaks

Van Hazendonk worked with “pencil shavings, but on the nanoscale.” These scraped graphite particles consist of multiple molecular layers, but Van Hazendonk demonstrated that Graphene Nano Platelets (GNPs) can successfully replace traditional metals, especially when extremely high conductivity is not required. “Take the disposable public transport chip card, for example, a paper ticket with a chip inside. You don’t want to use expensive materials for that. And GNPs can even be made from carbonized waste streams, which is an added sustainability benefit.”

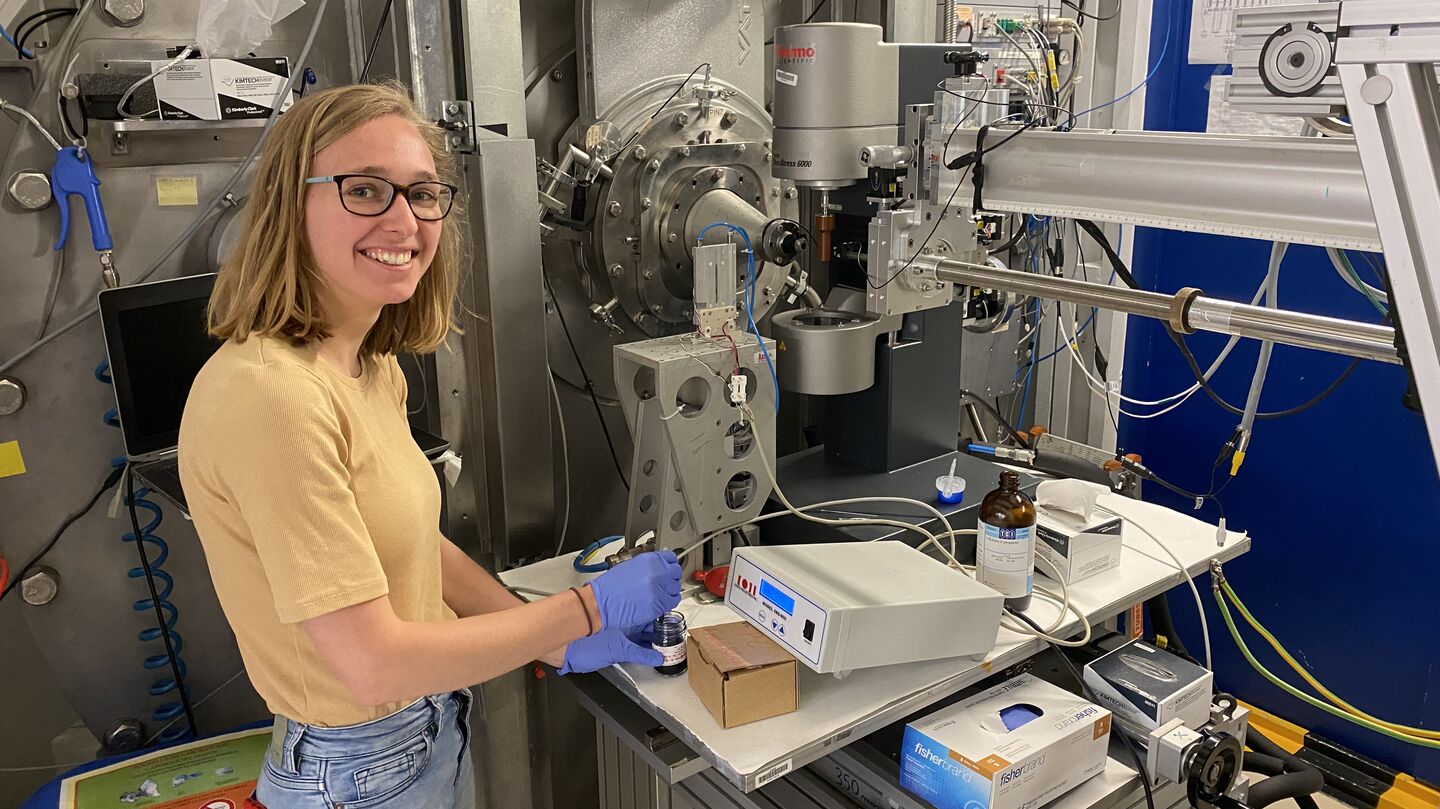

To develop a stable graphene-based ink, it’s crucial to understand the exact shape and dimensions of the scraped nanoparticles. Van Hazendonk therefore worked on a unique method to determine particle length, thickness, and diameter in a single measurement. “We expose a particle to X-rays, which then leaves behind a scattering pattern. From that, we can extract a wealth of information. What’s great is that this doesn’t just work for GNPs but much more broadly. We can now measure the dimensions of other plate-shaped particles, such as clay, more accurately, too.”

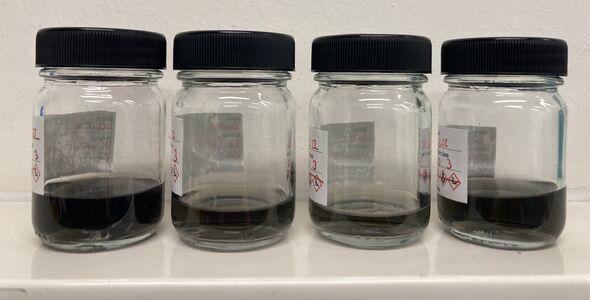

T-shirt with heart sensors

Thanks to this new measurement method, Van Hazendonk was able to experiment with the composition of GNP ink. “By varying the speed and duration of mixing GNPs, we can now produce all kinds of different GNP inks. Larger particles are better for conductivity—the bigger the particle, the better it conducts. But they can’t be too big, or they’ll clog the inkjet nozzle. It’s about finding the balance: do you want high-resolution printing or superconductivity?” Van Hazendonk smiles. “A giant pencil in a mega-mixer—that’s basically what I’ve been working on all these years.”

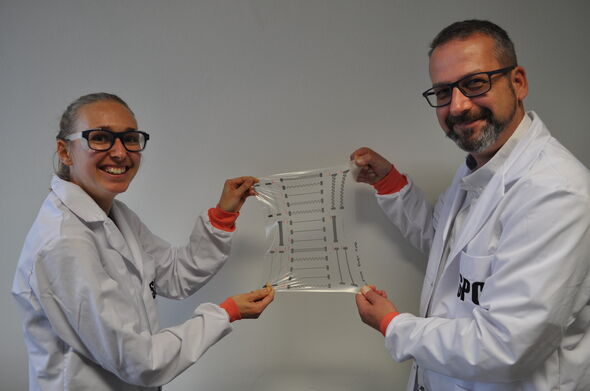

Within the European Graphene Flagship, Van Hazendonk and her supervisors collaborated with several partners to explore applications for GNP ink. “From surgical robot hands to clothing with breathing and heart sensors for medical or sports use. Even electrodes to stimulate plant growth. In all of these applications, we demonstrated that we can print high-tech electronics with GNP ink that’s skin-friendly, non-toxic to the environment, and far more sustainable than conventional methods.”

Political world

Sustainability is essential to Van Hazendonk on a personal level. Alongside her research project, she served as a member of the Provincial Council for GroenLinks starting in March 2023. “As a PhD candidate, you often work in a tunnel. For me, it was refreshing to also see the bigger picture. As spokesperson for energy & climate, transportation, and health, you deal much more concretely with societal relevance. At the same time, I brought a refreshing perspective with my ‘beta brain,’ although I also find it difficult that facts don’t always seem to matter.” She waves her list of dissertation propositions: “Science is too political, while politics is little scientific.”

A few weeks ago, she resigned as a council member due to “a combination of factors,” a decision covered by several media outlets. “Grieving, a PhD, a new job, and a new pregnancy. Within the strict rules on political leave, there simply wasn’t enough flexibility. It’s good that this is being discussed more openly now.” A bright spot among all the gray.

PhD in the Picture

What’s on the cover of your dissertation?

“An artist’s impression of the many shades of gray we saw during our measurements in Grenoble. It was fantastic to be able to use the radiation of the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility multiple times. In blocks of 24 or 48 hours, we could measure an entire series of graphene solutions. It was very special to suddenly see all those gray vials reflected in one of my father’s paintings.”

You’re at a birthday party. How do you explain your research in one sentence?

“I make ink from pencil tips to print electronics.”

How do you blow off steam outside of your research?

“The political work has always given me a lot of energy. And it helped me put things in perspective when experiments in the lab didn’t go as planned. If I had any time left after that, you could find me at the bouldering gym or the survival course.”

What tip would you have liked to receive as a beginning PhD candidate?

“Don’t put too much pressure on yourself in the first year—that year is really meant for learning. The results will come later, once the learning process pays off. You can’t always go full speed or be perfect. My son Ties taught me to let go of my perfectionism, which certainly helped me finish my dissertation.”

What is your next chapter?

“In June, I started at the energy team of CBS as a statistical researcher. During my PhD, I worked extensively with large datasets, and through my political portfolio I got to know the energy sector. It all comes together nicely this way.”

Discussion