Studying for a PhD in times of corona

How are Eindhoven's doctoral candidates faring during this corona pandemic?

As long as the labs remain open most young researchers can carry on as usual, although those who depend on test subjects are running into problems. The main source of concern is the mental health impact of the social restrictions; in particular on international doctoral candidates who are far from home. Having said that, there are also some bright spots for them, like the introduction of the hybrid PhD conferral ceremony.

Broadly speaking, the problems faced by doctoral candidates are less severe than we might have feared, ventures Dean Paul Koenraad of the TU/e Graduate School. “This has been revealed by, among other things, a stocktaking exercise carried out on the initiative of the PhD-PDEng Council.” Nor has he seen a sharp rise in the number of extensions being applied for. “Those who were due to gain their PhD this year were busy writing back during the lockdown. Logically, any extensions are more likely to fall among doctoral candidates who were then nearing the end of their third year and busy with their final measurements. We will find out next year whether this group does indeed need extra time.”

The labs were closed for some two months as of March 13th. Since early May practical work has been resumed, at some departments in two shifts per day to enable all their researchers to work safely in the labs. So the delay to doctoral candidates will be no more than two months, says Koenraad. The few individuals who were carrying out a long-term experiment involving living organisms are, he believes, the exception that proves this rule. ”As it did for many plants on the campus, the lockdown spelt disaster for these organisms.”

Those still encountering practical problems tend to be doctoral candidates who work with test subjects. In addition, he is finding growing concern among young researchers the longer the second wave of infections continues and fears of a possible second lab closure mount.“In the event of stricter measures being introduced, we could expect education to first be scaled down,” the dean stresses, however. “Doctoral candidates were the first to be allowed back into the labs in May and, if it comes to it, they will be last to be asked to leave this time around.”

Doctoral candidates were the first to be allowed back into the labs in May and they will be last to be asked to leave this time around

The greatest source of worry for Koenraad at the moment is the mental impact of the corona measures on his doctoral candidates. “For our international doctoral candidates in particular, who make up more than 60 percent of our PhD and PDEng students, this is a very difficult time; having to spend their days in a small room far from family and friends. Nor were many of them able to travel home this summer and so they simply worked on through the vacation period. In these exceptional circumstances therefore, they are being allowed to carry all their vacation days forward to next year.”

The end of the period of doctoral study is traditionally the time for the formal defense of the thesis before a special committee, an event that is followed by a large party. Now that corona has made such gatherings subject to all kinds of changing restrictions, by necessity the past months have seen plenty of experimentation with online and hybrid ceremonies. For almost everyone, the wholly online ceremony is an unfavorable solution born of necessity, admits Koenraad. “Although for some international doctoral candidates who had already returned to their home countries, it proved a welcome solution.”

Hybrid defense ceremony

The hybrid version, in which the doctoral candidate, supervisor(s), paranymphs, (some of) the doctoral committee and a select company of guests are present on the campus and the others - who often include foreign members of the doctoral committee - attend the ceremony via a digital link, is here to stay. This is the dean's view. “Once we have mastered the technical aspects, and have good sound and multiple cameras managed by an operator, the hybrid PhD conferral ceremony certainly becomes a very practical option. Family and friends from abroad can easily attend and it also makes it easier to have academic ‘hot shots’ from abroad on the doctoral committee.”

I've got my doubts about starting a new experiment because I'm worried that I'll have to stop when I'm in the middle of things.

While since May most doctoral candidates have been able to get the lab time they need, those who work with test subjects are still dealing with restrictions. This is an issue primarily at the departments of Industrial Design and the Built Environment and, to a lesser extent, at Biomedical Engineering and IE&IS.

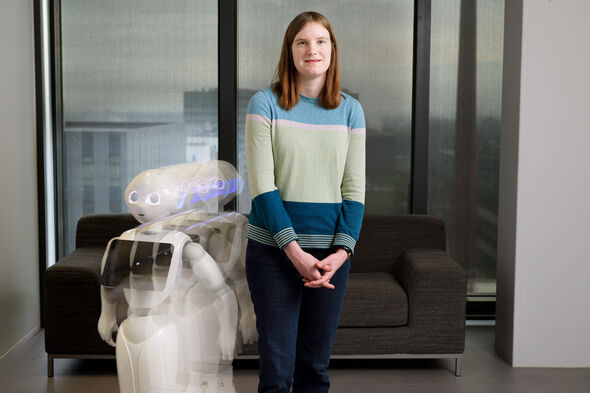

Doctoral candidate Margot Neggers carries out her research in the Social Robotics Lab (IE&IS), studying how people respond to robots. Since September the lab has been open to test subjects, but working with them now involves adhering to a strict protocol. Thus, for example, only one person may be in the lab at any one time; instructions are given over the intercom from an adjacent control room. “I use what are called location trackers set in a headband to follow the movements of test subjects when they are confronted with a robot passing by them. It's a quite a hassle if I want to help them put on the head band.”

This is because location trackers, virtual reality glasses or sensors like heart rate monitors can only be attached to the test subject by researchers wearing gloves, a face mask, and a face shield or goggles, as prescribed in the corona protocol. Virtual reality glasses must first be cleaned with isopropanol then treated with UV light before being inserted into a disposable sleeve. And on top of all this, test subjects must wear a hairnet, even if they have no hair.

Over sixty

Despite these precautionary measures, test subjects aged over sixty are no longer welcome, Neggers tells us. “This is a pity; our test subjects are often students or retired people. So now our pool is a lot less varied.” In any event, the number of experiments in the Social Robotics Lab is still very minimal, she explains. “Our students have been working a lot with questionnaires and short films instead of with physical experiments. Unfortunately, for my own research this won't do.”

Until now Neggers has devoted much of her time to analyzing measurements taken before the lockdown. “Now that work is all done. But I've still got my doubts about starting a new experiment because I'm worried that if stricter measures are reintroduced I'll have to stop when I'm in the middle of things.”

Chiara Raffaelli is a PhD candidate at the Department of Applied Physics. As she is working on a theoretical subject, she has been working entirely from home since the start of the first lockdown in March. “I’ve been to the office only once,” she says. “But that felt really awkward, what with having to keep your distance. And it meant I couldn't be sure that I would be allowed to sit at my own desk when I returned. Even with the measures in place, it felt like taking a risk so I decided to stay home altogether.”

The Italian researcher is living alone in a small apartment in Eindhoven. “I have one table where I eat my meals, do my work and do everything else. I sit there with the kitchen right behind me.” Spending days on end in a space measuring two by two meters can be tough, she says. “It feels like I am never fully working nor entirely free. During the first month of the lockdown I would pack up all my work stuff at night, but in the end I gave up doing that.” Still, she does not want to complain. “I know many people are much worse off. I have a job and I am healthy. Complaining makes me feel guilty.”

Traveling

She has been living away from her home country for quite some years now, so it is a situation she is used to. “It does feel different, though, to know that you can’t travel home easily. Even if you weren’t planning to.” Raffaelli has seen her boyfriend, who is living in the UK, only once since the start of the pandemic. “I’m used to a long-distance relationship, but we had been travelling to meet up at least once a month. Unfortunately, that’s not possible now.”

Being a sociable person, she also used to take the train to visit friends around the country at weekends. “Now on the rare occasions that I meet up with someone - as I did last summer - I feel guilty because I really don’t want to spread the virus. I feel anxious about these things all the time. Should I visit my family back in Italy during the Christmas break or would that be irresponsible? My father is in the risk group but he has to be in touch with people for his job, so I am more worried that my parents will get sick now than I was during the full lockdown in Italy in the spring.”

Numb

The situation clearly affects her mood, as Raffaelli admits. “I notice that small negative things hit me quite hard at the moment. Generally, I feel rather numb, and I feel the same way about the problems I might have to face looking for a job after finishing my thesis, which should be finished in a few months' time. I am struggling to write my thesis, but I must say I don’t know to what extent this is due to the current situation. At any rate, writing a thesis is hard for most PhD candidates. My job feels quite useless when some days I accomplish nothing and no one will notice anyway, apart from my supervisor at our next weekly session.”

Mental support

Even before the corona pandemic had the world in its grip, the university had decided that doctoral candidates could use more centrally-offered support. As a result, counselor Stijn van Puijenbroek and psychologist Nicole van der Knaap are now available to help with their worries and other issues related to mental health.

Stijn van Puijenbroek started work in September as a counselor for PhD and PDEng students, a role in which he is neutral contact person for doctoral candidates with all kinds of questions and problems. “In many cases, a short and freely accessible one-to-one session is all it takes to get a handle on some matters. What is feeding my frustration? Why do I feel unhappy? Sometimes the problems are severe and I will refer the student to psychologist Nicole van der Knaap, but working with someone to order your thoughts is a simple step that can really help.”

Doctoral candidates sharing an office, lab or coffee maker often provide each other with a listening ear, the chance to vent worries and frustrations. Now that they too have been working from home for a number of months, this daily social contact has dropped off in many research groups. This is the impression Van Puijenbroek has. And it is gradually taking its toll. “You can help relieve this problem by setting regular times to meet up online. And there's the added benefit that these dates bring more structure to your working week.”

Weekly schedules

This structure is more important than ever when you are working from home for weeks on end, he stresses. “My advice is often to make a weekly or even a daily schedule in which you allocate time for both work and personal activities. This provides a framework and avoids the sense of drifting through the days. And then on Friday, you celebrate your successes and plan whatever you haven't managed for the following week.” Van Puijenbroek advises not to carry a problem around for too long. “Don't wait until you end up in a crisis, instead talk to a colleague or make an appointment with me.”

Even without corona, social contact is an issue for international students and doctoral candidates, with friends and family far away. And although in many cases they are used to spending a lot of time online talking to their loved ones, in the current situation internationals have a harder time making ‘real life’ contact and in the Netherlands they have no network to fall back on. “Given this, it can be pretty hard-going when your family is in India, where conditions are now difficult, and you are worried about your sick grandmother.”

Vicious circle

Nicole van der Knaap has been in her present role as a psychologist supporting doctoral candidates since her appointment on April 1st. She emphasizes that international doctoral candidates are certainly not alone in needing help. “Motivation problems, especially, also occur among Dutch doctoral candidates. At home they are facing more distraction and have less structure, so it is now proving harder for them to keep on working.” This can lead to a vicious circle, she says. “Once you realize you aren't making headway, you feel stressed, and this has only an adverse effect. And seated at your computer it is always easy to find a distraction in order to escape the tension for a while.”

The people who are having an exceptionally hard time of it at the moment are, she says, the internationals who had no time before the corona pandemic to build a social network. “Despondency can sneak up on you if you spend entire days sitting alone in your studio apartment. So I always advise them to keep actively seeking contact with whoever they already know here, and with their family and friends back home. I see doctoral candidates who are working from early in the morning until late at night, but it's really important to take time to relax and, above all, to get some exercise.”

In recent weeks she has seen another rise in mental health issues, says the psychologist. “The announcement of the present ‘light lockdown’ immediately prompted a rise in requests for help. Those who had found hope in the period when things started getting better again and we could all do more are now suffering yet again from the enforced homeworking and uncertainty about whether experiments are still possible. They were treading water and are now in danger of going under.”

Van der Knaap endorses the plea not to wait until mental health issues get worse. “Prevent yourself getting into a downwards spiral. Get in touch with us. We are keen to help you.”

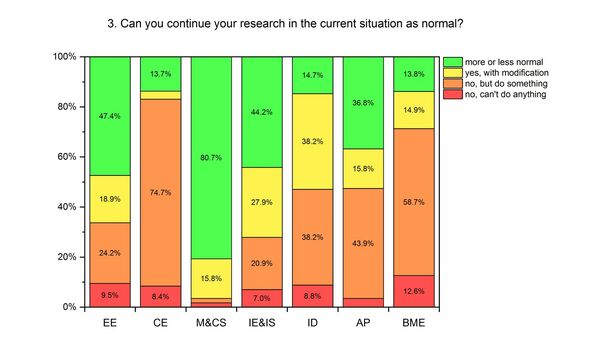

Spring lockdown survey

During last spring's lockdown a survey was held by seven departmental PhD-PDEng Councils (every department except for Built Environment and Mechanical Engineering). This has clearly revealed that the impact of the corona measures on doctoral candidates depends heavily on the nature of their research and thus varies from department to department. Computer or theoretical work could often be continued as per normal; at Mathematics and Computer Science it seems that as much as 95 percent of doctoral candidates experienced little nuisance and similarly at IE&IS three-quarters of the respondents indicated they could get along well.

Doctoral candidates at departments with a great deal of lab work had a more difficult time. At Chemical Engineering and Chemistry the laboratory closure presented no difficulties for only 15 percent: three-quarters indicated they had turned to other work out of necessity - such activities as analyzing measurements, doing a literature study, making models and writing articles. A small percentage, rising at Biomedical Engineering to more than 12 percent, expressed that they had been entirely unable to work on their research during the lockdown.

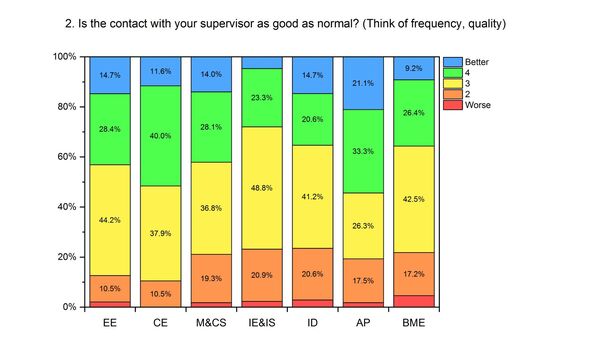

Another striking survey finding is that during the spring lockdown many doctoral candidates had better contact with their supervisors than they had previously. At Chemical Engineering and Chemistry as many as half indicated their contact had improved, and for only 10 percent did the quality of the contact deteriorate. At none of the departments surveyed did the proportion for whom contact with supervisors had deteriorated exceed 20 percent. In addition, the university's communication about the corona measures was rated across the board as positive.

In November a survey will again be held by the Graduate School in conjunction with the central PhD-PDEng Council. This, says Dean Paul Koenraad, will also inquire into the well-being and welfare of doctoral candidates.

Discussion