Walking, running and cycling: 1.5 meters is not enough

Keeping a 1.5 meter distance is not effective when people are walking, running or cycling. This is the conclusion of professor Bert Blocken based on aerodynamic research. The preliminary publication of his findings attracted global media attention, but there is sharp criticism as well. Blocken: “I will resign if the study is incorrect.”

He hadn’t exactly foreseen the media storm that broke out. “Suddenly, I get media requests from Australia and Japan as well as the US and Canada,” Blocken emails. “That will keep me busy for some time.”

The findings of the study he published in a white papera few days earlier are already starting to gain worldwide attention at that point. His research focuses on social distancingduring walking, running and cycling. Just when everyone is getting used to the 1.5 meters measure, his conclusion is that this distance is not enough in certain situations. At least, not if you look at the distance droplets carrying the coronavirus can travel from our mouths. According to Blocken, people would do well to keep a distance of four or five meters when walking behind a slow walking pedestrian. In case the person in front of you is a jogger or a cyclist, he advises ten meters, and twenty meters for racing cyclists. He doesn’t want to cause a panic, Blocken emphasizes, but the results speak for themselves. However, some scientists, mostly virologists and epidemiologists, challenge his conclusions. They say that the risk of infection is hardly higher in practice.

Wheelsucker

Blocken, professor of Aerodynamics at the universities of Eindhoven and Leuven, has spent many years investigating the movement of droplets in streams, and how airflows swirl around objects. His study into the slipstream of cyclists drew international attention eight years ago. A wheelsucker (a cyclist who rides closely behind the leader) can make cycling slightly less strenuous for the lead cyclist, he concluded. His current research is comparable to such ‘slipstream research,’ Blocken says.

“Eight months ago, we worked on a project in which we measured and simulated particles in our wind tunnel in Eindhoven. We combined that with wind tunnel experiments from Indian colleagues, who measured how droplets move in a certain airflow and how they evaporate and become smaller.” That, combined with existing data on droplet dispersion when breathing, was processed in a computer model by Blocken and his colleagues.

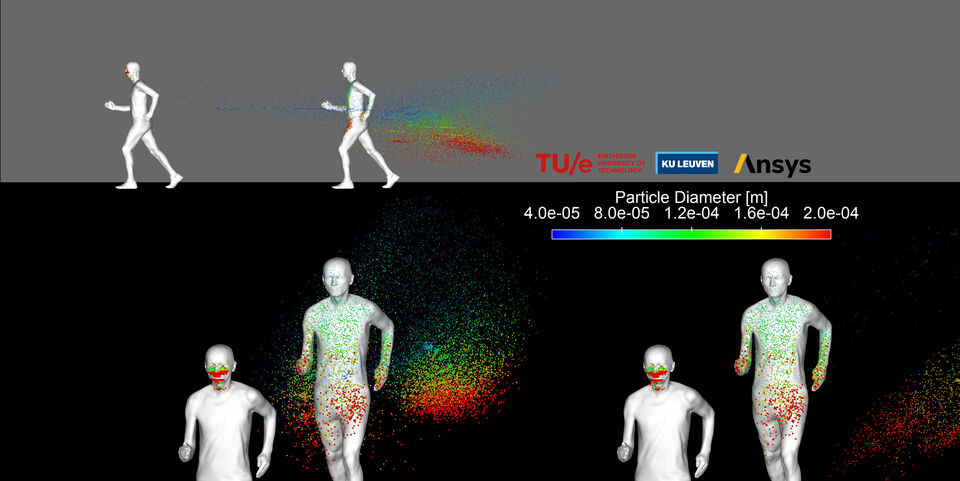

Images clearly show how a spray of droplets moves from the person in front to the person right behind. The larger droplets, which are the most infectious according to virologists, mostly reach the groin and the hands - less of a risk than in the face, but still undesirable.

Criticism

Blocken’s research does not just stir up commotion among journalists. Colleagues from different fields express their support on social media, but interestingly enough there are also some sharp remarks, heated reactions, and reactions to reactions. The simulation model used by the researchers from Eindhoven and Leuven supposedly wasn’t realistic, the boundary conditions weren’t sound, and so on. “Many reactions are based on misunderstandings,” Blocken says. “For example, one person wrote that it is a bad sneeze simulation, but we don’t simulate sneezing at all.”

Blocken is a bit surprised by the fierceness of some reactions. “Some people even claim that my research is a public health hazard, while my conclusions don’t differ that much from what you can come up with using common sense. When you exhale droplets and walk forward, those droplets will remain in your slipstream. Simple and logical.”

Nevertheless, the commotion and resistance caused by Blocken’s publication isn’t that surprising. The study wasn’t peer reviewed, meaning that is wasn’t checked by colleagues in the field, as is common practice. Instead of an extensive description of the methodology and results, the text consists merely of a short summary of less than three pages. That’s practically asking for misunderstandings about the chosen approach.

Unethical

Blocken acknowledges that they deviated quite a bit from the golden standard in science, to put it mildly. They did so because the conclusions seemed logical and undisputable to them. And in addition, the conventional method would have been far too time consuming. “I discussed that with the research team and we unanimously agreed that it would have been very inappropriate, unethical even, to wait six to eight months before coming forward with these results. To say: 'sorry, we could have told you eight months ago, but we thought our publication was more important'.”

Blocken isn’t the only one with such an unorthodox approach at the moment, scientists all over the world are temporarily flouting the generally accepted standards. There is a veritable explosion of publications because the slightest bit of information might save lives. “In the US they test medicine on people now without following the normal procedures of publicizing or testing on animals first. These just happen to be unusual times.”

Hate mail

Blocken has by now published a more extensive article online, which does meet all the requirements. He trusts that this will silence criticism in time. In the meantime, he’s willing to accept the ‘hate mail.’ “People write that I’m incompetent, an alarmist, and use other strong words I rather not repeat. At the time, I had the same experience with the cycling research, with which I also came forward before the official publication. I also received many comments on that, but eventually everything turned out to be right. I don’t mind if you write this down: I will resign from both universities should the study turn out to be incorrect. I think this is a matter of honor, ethics and reputation.”

Discussion