Home stretch | Examining the promise of green hydrogen

PhD researcher studies global collaboration in the energy transition

Green hydrogen is often seen as a key technology for decarbonizing heavy industry and reshaping global economies. But can it truly live up to expectations? In her PhD research at TU/e, Clara Caiafa explores how international collaboration, local benefits, and trust between countries could help make it a fairer and more practical part of the energy transition.

In 2022, a surge of momentum for green hydrogen inspired her doctoral research. “Green hydrogen was seen as the way forward in the energy transition and in decarbonising heavy industry,” says Clara Caiafa. Hydrogen plays a key role because it can store renewable energy and produces no CO₂ at the point of use.

Green hydrogen is produced by splitting water into hydrogen and oxygen using electricity from renewable sources, for example from wind or solar power. The challenge is that countries like the Netherlands require more green hydrogen to decarbonize their industries than they can produce themselves.

“If you were to use green hydrogen to decarbonize steel production at Tata Steel in IJmuiden, you would need about 18 percent of the Netherlands’ current electricity production — and that’s on top of all the additional demand we would need for electric vehicles, heat pumps, and other industries,” Caiafa explains. “It would be very challenging to meet this demand fully with domestically produced hydrogen.”

Collaboration

This is one reason importing green hydrogen became a key strategy. Countries with abundant and cheap renewable energy resources—such as strong sun, steady wind, or ample space for renewable energy infrastructure—are therefore particularly well suited for large-scale green hydrogen production, potentially becoming future exporters of clean energy.

International collaboration can connect countries that need green hydrogen to decarbonise their industries with those that have the most suitable conditions for production. In her doctoral research, Caiafa examined what such collaborations would mean for economies, particularly in developing countries.

Brazil

One concrete example of international collaboration is a partnership between the Dutch government and the Brazilian state of Ceará, aimed at setting up a green hydrogen production hub. “That was the perfect case study to see how this works in practice,” Caiafa says. “And since I’m Brazilian, I know both countries well and speak both languages. I could interview stakeholders in both countries to understand local perspectives and spot potential gaps between policy and practice.”

“There’s so much nuance in politics,” she adds. “Knowing the country where you conduct your case study is a huge advantage. That made this a perfect opportunity for me.”

Exploitation

Such international collaborations can bring significant benefits, but they also carry clear risks. The key challenge is to ensure that wealthy countries do not benefit disproportionately, simply by sourcing cheap green hydrogen produced elsewhere. In that case, the energy transition risks becoming little more than a modern form of exploitation.

According to Caiafa, it is therefore essential that developing countries genuinely benefit at the local level. In practice, this means embedding green hydrogen production in ways that create local jobs, strengthen domestic economies, and enable knowledge and technology transfer. Only then can international cooperation on green hydrogen contribute to a fair and inclusive energy transition, rather than reinforcing existing global inequalities.When WWBottom of Form

Unanswered questions

Producing green hydrogen at scale also raises many unanswered questions, her study reveals. For example, some countries have abundant wind and solar resources, but their grids still rely heavily on fossil fuels, and many regions around the world lack access to electricity. “Given the energy required, some argue it might be better used locally—to electrify households or decarbonise the domestic grid—rather than produce hydrogen for export,” she says.

Shipping hydrogen over long distances also presents major challenges. Hydrogen is a gas and must be liquefied for transport, which requires significant energy. The shipping process itself is energy-intensive, making it costly and reducing the potential emissions savings. An alternative to importing hydrogen would be to relocate industries closer to where green hydrogen is produced, allowing products to be made right at the source.

Steel industry

In the second part of her thesis, she looked at the socio-economic and climate impacts of two options: importing green hydrogen to the Netherlands to decarbonize the steel industry here, or moving the industry to Brazil and then importing the steel. Her analysis included both local impacts and effects on the Dutch economy, as well as impacts on greenhouse gas emissions globally.

She concludes that importing liquefied hydrogen from Brazil is not a good idea. “It is significantly more costly and reduces potential emissions savings, making it the less favorable option from a climate perspective.” Higher costs would also affect downstream industries that rely on steel, such as the automotive sector, potentially endangering their competitiveness. Producing steel in Brazil, on the other hand, would be more cost-effective, while also creating jobs and stimulating local economies.

“Although I studied a specific case, I believe my conclusions are more broadly relevant,” she says.

At the same time, she acknowledges challenges linked to relocating industries, particularly dependence on other countries and loss of autonomy. “Note that defense relies on the steel industry, so moving it far away could make a country vulnerable. In the current geopolitical situation, this becomes a delicate issue.”

Trust

Still, she believes the topic deserves further examination. “Maybe we don’t need to go all the way to Brazil. The Netherlands could work with countries like Italy or Spain, which have fewer constraints on renewable energy,” she says.

She stresses the need for more proactive and strategic approaches from governments. “Simply exporting green hydrogen won’t transform the economies in developing countries. Developed countries like the Netherlands, on the other hand, need to realize the world is changing. They must actively shape their industrial and energy policies, in response to shifting global power and supply chains, instead of relying on outdated assumptions.”

More research on different scenarios is essential, she adds, so policymakers can understand the costs and what might actually work.

“Ultimately, large collaborations between countries are also about trust—especially when outcomes are uncertain or when dependence is involved. Fostering trust is difficult right now, but European countries need to come together. We might seek autonomy, but together we can achieve far more than any single country could on its own.”

PhD in the picture

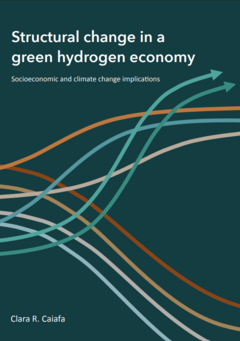

What’s on the cover of your dissertation?

“Those arrows are often used in studies on innovation. They represent new technologies that emerge and, at a certain point, clash with existing ones, pushing the whole system to transform. Some of the emerging technologies make it to the top, others collapse, and some existing technologies manage to adapt and continue. Eventually, they realign and stabilize. But when it comes to hydrogen, we are not there yet, which is why the illustration does not show where the arrows end.”

How would you explain your research at a birthday party in one sentence?

“I study the socio-economic implications of energy transition.”

How do you blow off steam outside the lab?

“I’ve started rowing, which I really enjoy. It’s nice to be on the water without even touching it, and to spend time outside. I’ve also taken up sewing. As a Brazilian living in the Netherlands, I always need to shorten my pants, so it’s a skill that really comes in handy,” she says, laughing. “It’s also nice to buy second-hand clothes and be able to alter them so they fit.”

What advice would you give your younger PhD self?

“People pursuing a PhD tend to be very structured and follow clear steps, but more often than not, things don’t work out that way. So it’s essential to stay open, be flexible, and trust the process.”

What’s the next chapter?

“I’m staying here as a postdoc, focusing on the same topic but more in the Dutch context. I’ll also be teaching, and I’ll work as an author on IPCC reports, contributing to the chapter on industrial decarbonization, which is closely related to my research and very rewarding.”

Discussion