Home Stretch | Better images through smart sound

Cognitive ultrasound aims to make razor-sharp images possible for everyone

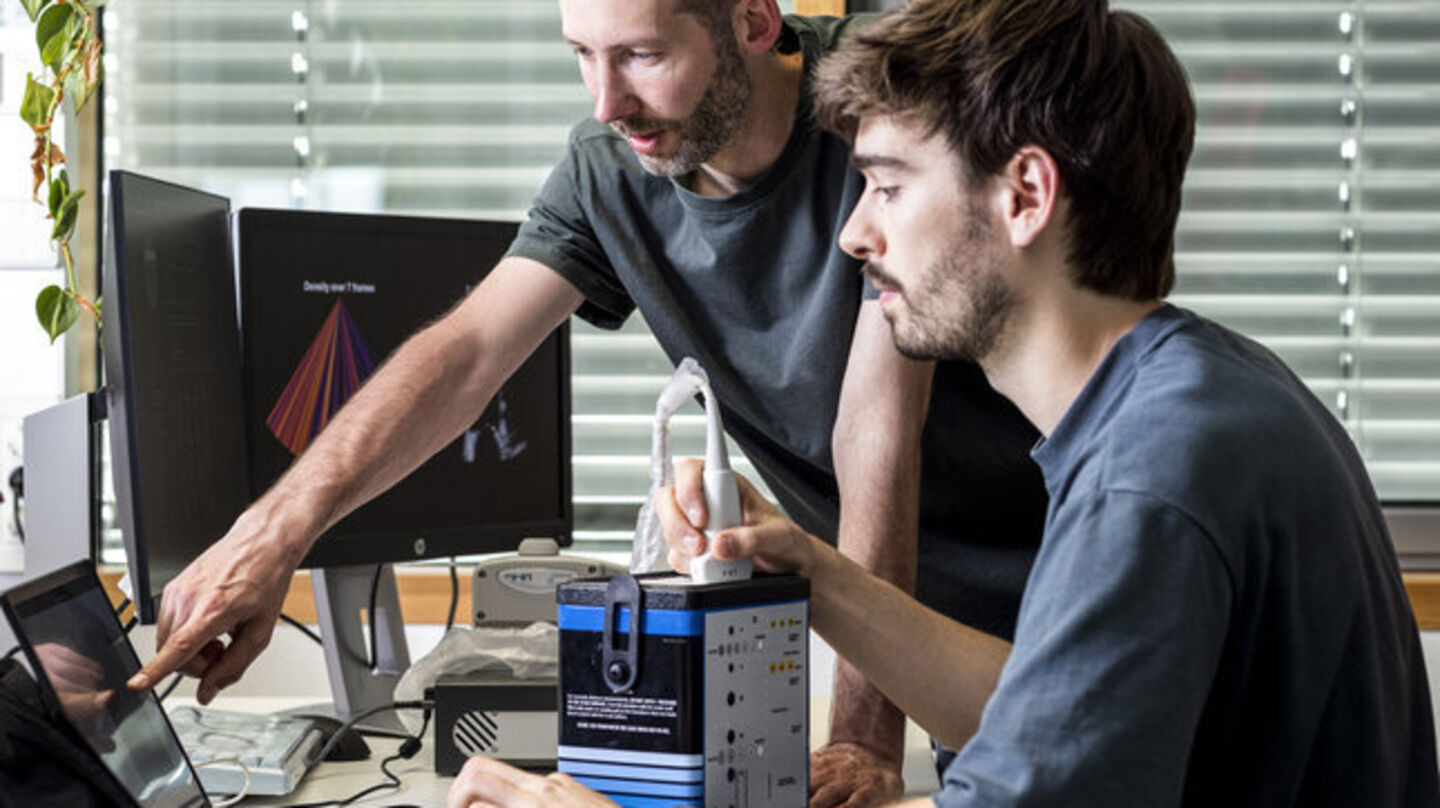

Sharp ultrasound images in ambulances, smartphone-based ultrasound, and better prenatal scans in countries with limited healthcare are coming within reach. Using a new approach to signal processing and deep generative models, TU/e researcher Tristan Stevens is improving both the quality and applicability of medical ultrasound. Today, he defends his research at the Department of Electrical Engineering.

At the start of his PhD trajectory, Tristan Stevens spent time at the Catharina Hospital, working alongside the Radiology department. It was an eye-opener. While undergoing an ultrasound exam may be barely taxing for a patient, the job involves much more for a radiology technician.

“It’s really physical work. Pushing, twisting, often under time pressure. Ultrasound exams come one after another,” he says. And with an increasingly diverse patient population, the challenges in the ultrasound room are growing as well.

One example, Stevens explains, is performing an ultrasound on a patient with a high BMI. “Sound waves are reflected differently by fatty tissue, which leads to more noise in the ultrasound images. That makes it harder to quickly find the right location, and the final images are also much less clear.”

First, a quick lesson in ultrasound. Using a special device—the transducer—high-frequency sound waves are sent into the body. These waves bounce off organs and tissues.

The transducer then captures the echoes and converts them into an electrical signal. Ultimately, the system processes the various measured signals into a visible ultrasound image on a screen.

Connecting factor

“Making an ultrasound image may seem simple. But there are many steps involved before you see the final image. Until now, those steps have been studied and improved separately. In our Signal Processing Systems group, we are taking a completely new approach.”

“We look at how those separate components can inform and influence each other. Using smart algorithms, we calculate away the disruptive noise, which should lead to more reliable ultrasound images.”

An ideal project for Stevens, a natural connector who enjoys bringing people and information together and dislikes silos. At the start of his PhD, he also helped bring together the TU/e chess community as a co-founder of the student chess association Noesis.

“I get a lot of energy from working together. In a research setting, that can offer a refreshing perspective—exactly what you need for out-of-the-box innovation.”

Self-thinking ultrasound device

In recent years, major steps have been made in this field by the research group led by Ruud van Sloun, one of Stevens’ supervisors. According to Stevens, they are now close to a first concept of cognitive ultrasound. In this approach, an ultrasound device determines for itself—based on smart algorithms—which measurements should be taken. Sound waves are then directed toward the location with the most relevant information.

A breakthrough in medical image processing, Stevens emphasizes enthusiastically. “To achieve this, we work with so-called deep generative models. This is a form of artificial intelligence that uses deep neural networks to learn the structure of data and, based on that, can generate new content.”

“Much like ChatGPT predicts which word comes next based on patterns in large datasets, these models can predict which echo signals are most likely, allowing them to suppress noise or reconstruct missing information.”

Dynamics

To train his models, Stevens used specific ultrasound data from collaboration partner Philips Research. The focus was on cardiac ultrasound—both because the heart is highly dynamic, which makes it challenging, and because there are many people with cardiovascular diseases. But, Stevens stresses, other forms of ultrasound imaging can benefit from this technology as well.

Stevens flips through his dissertation and shows several ultrasound images of a heart. “With this new model, we see a clear improvement in image quality. This also applies to more complex ultrasound imaging, such as in the growing number of patients with obesity.”

Investing in coding

His research is highly technical, Stevens says. At the same time, he is keen to help pave the way for actual clinical application. To accelerate innovation, Stevens therefore built a new open-source software platform, zea.

“Around me, I found a lot of expertise, but all in separate pieces. Now I’ve brought together all the ingredients you need for smart ultrasound: models we’ve trained, tools to train your own models on ultrasound data, and methods to determine what you should measure next to create the following image.”

Developing such a platform is a substantial investment, the Electrical Engineering PhD candidate adds. “At the university, you’re assessed on the number of papers you publish. Code or a platform you build is seen as a byproduct. While that is also very important—it saves everyone a lot of valuable time if, after reading a paper, you can immediately get to work. Fortunately, there is growing appreciation for that.”

Smartphone ultrasound

For zea, Stevens did not use the programming language commonly used within the ultrasound community, but instead relied on state-of-the-art machine learning code in Python. According to him, the major advantage is that new technological developments from computer science can be directly applied to collecting and processing ultrasound signals.

This makes the effect on image quality immediately visible, Stevens explains. And it brings portable ultrasound equipment—allowing you to make reliable ultrasound images with your smartphone—a step closer to the quality of a full-fledged hospital scanner. He lists a few more examples. “Sharper ultrasound images in ambulances, even for patients with severe obesity. Or better prenatal ultrasounds in countries with limited healthcare.”

“A nice bit of legacy,” he smiles. “We’ve shown that deep generative modeling is a powerful tool that appears promising for successful application in ultrasound imaging, even for raw data. Many colleagues are already using the new platform. A small building block toward making the ultrasound of the future smarter.”

PhD in the Picture

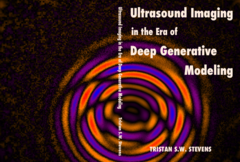

What do we see on your dissertation cover?

“Two ultrasound waves, one desired and the other not. They interfere with each other, creating a beautifully complex pattern. With each chapter, that pattern becomes more complex, which challenges us to extract the right information from it. Quite poetic, right? I even wrote a poem about it, as a closing piece on the last page of my booklet.”

You’re at a birthday party. How do you explain your research in one sentence?

“I try to improve the images produced by medical ultrasound. People usually have an immediate reference—everyone knows prenatal ultrasounds.”

How do you unwind outside of your research?

“Playing the guitar! I prefer making music together, for example with my band Jazzal. And every now and then a game of chess, or outdoor climbing when the weather is good.”

What tip would you have liked to receive as a starting PhD candidate?

“In the early years, don’t be afraid to color outside the lines. Collaborate a lot, take initiative. At the start of my PhD, I took part in a conference challenge, and we created an award-winning ultrasound image of the vascular system in a rat brain using microbubbles. That ‘side trip’ definitely gave me opportunities that strengthened my main research path.”

What is your next chapter?

“I’m staying in the same research group, now as a postdoc. But on a completely different project, in which I deliberately sought out industrial collaboration. With ASML, I’ll be applying deep learning modeling to signal processing problems in semiconductor manufacturing. Still waves—but now light instead of sound.”

This article was translated using AI-assisted tools and reviewed by an editor.

Discussion