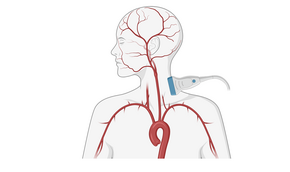

Home Stretch | Blood flow visualized with ultrasound in neck

Carotid ultrasound as a new way to monitor patients’ circulation

To monitor patients during and after surgery or in the intensive care unit, clinicians use catheters to keep a close eye on the circulatory system. TU/e researcher Esmée de Boer shows that ultrasound imaging of the carotid artery is a promising, less invasive alternative. Today, she is defending her PhD dissertation at the Department of Electrical Engineering.

While other PhD candidates put on their lab coats and spend afternoons running experiments among research setups, chemical substances, or petri dishes filled with cells, Esmé de Boer’s work looked slightly different. She followed a strict sterilization protocol, dressed in blue operating room attire and a purple hairnet, before being allowed into the operating room at Catharina Hospital. During many surgeries, the technical medicine specialist – she graduated from the University of Twente – stood next to the anesthesiologist to take measurements from patients. She shrugs with a smile. “It sounds more exciting than it actually is.”

A well-functioning circulatory system is essential for good health, De Boer explains. “Vital organs need a constant supply of oxygen, which the heart pumps through the bloodstream. That’s why doctors in hospitals closely monitor the status of a patient’s circulation. This can be during or after surgery, but also, for example, in the intensive care unit.”

The current ‘gold standards’ for so-called hemodynamic monitoring are very accurate, but also demanding for patients. “In these methods, the physician inserts a special catheter into the bloodstream toward the heart, sometimes even into the heart itself. That comes with an increased risk of various complications.”

“In a collaborative project between TU/e, Catharina Hospital, and Philips Research, we are therefore investigating how we can monitor patients’ circulation in a less invasive way, with the same level of precision.”

Rotating and tilting

Together with several fellow PhD candidates, De Boer has spent the past four years developing new techniques to monitor circulation using carotid artery ultrasound. The first results are promising, she says enthusiastically. “The carotid arteries are close to the heart and are easily accessible, even in, for example, patients with obesity. We were already able to visualize the carotid artery well using ultrasound, but now we are demonstrating its applicability in clinical scenarios.”

To achieve this, De Boer first had to find the optimal position for the ultrasound probe. “In short carotid examinations, the probe is usually placed in line with the blood vessel. But for continuous monitoring, that didn’t work well; movements by the patient or the clinician meant we couldn’t keep the carotid artery clearly in view at all times. By rotating and tilting the probe, we eventually managed to do just that.”

Ultrasound patch

Using this new approach, De Boer collected a large amount of patient data in the operating room. From this, she extracted several parameters that turned out to be relevant for understanding what is happening in a patient’s circulation. “Of course, we look at the pulsating changes in the diameter of the carotid artery with each heartbeat. But we also derive indicators from the velocity of blood flow, which allow us to perform calculations.”

According to De Boer’s studies, these parameters provide a reliable picture of circulatory dynamics, in several situations comparable to current, more invasive monitoring methods. “This new way of measuring has clear potential and could, in the future, replace catheter-based methods in a number of clinical applications.”

The studies are still relatively small-scale, De Boer emphasizes. Much more technological optimization and automation are needed before clinicians can actually use her innovations in practice.

“But we see that carotid ultrasound can add real value. Also for new healthcare innovations. Think, for example, of replacing the traditional ultrasound probe with a smart patch containing an ultrasound sensor. More comfortable for the patient, more efficient for clinicians; these small steps could ultimately make healthcare even better.”

PhD in the Picture

What do we see on the cover of your dissertation?

“The design is a bit futuristic; I wanted to show that my research cannot be applied just yet, it really is still about the future. With lots of color, which suits me. To emphasize the female patient in biomedical research, I chose a woman’s head; the ultrasound patch on her carotid artery reveals all kinds of information. On the back, you see the operating room where I spent many hours.”

You’re at a birthday party. How do you explain your research in one sentence?

“I’m looking at whether ultrasound images of the carotid artery can help us better monitor how a patient is doing.”

How do you unwind outside of your research?

“I love experimenting in the kitchen by making beautiful cakes—the more complicated, the better. With lots of layers or special decorations. I hope I’ll have a bit more time for baking again now.”

What tip would you have liked to receive as a starting PhD candidate?

“Don’t get too lost in the details; try to keep a helicopter view. With a perfectionist personality, that can be quite challenging.”

What is your next chapter?

“I’ve been working since this summer as a technical consultant at Performation. We develop software to support healthcare institutions, for example by mapping how much staff, how many beds, or how many operating rooms a hospital needs. Think of digital dashboards for nurses on the floor, or planning tools for policymakers and the finance department. That bridging role between technology and healthcare really suits me.”

This article was translated using AI-assisted tools and reviewed by an editor

Discussion