Home Stretch | Smart lipid nanoparticles awaken immune cells

Mixing molecules to better control RNA therapy

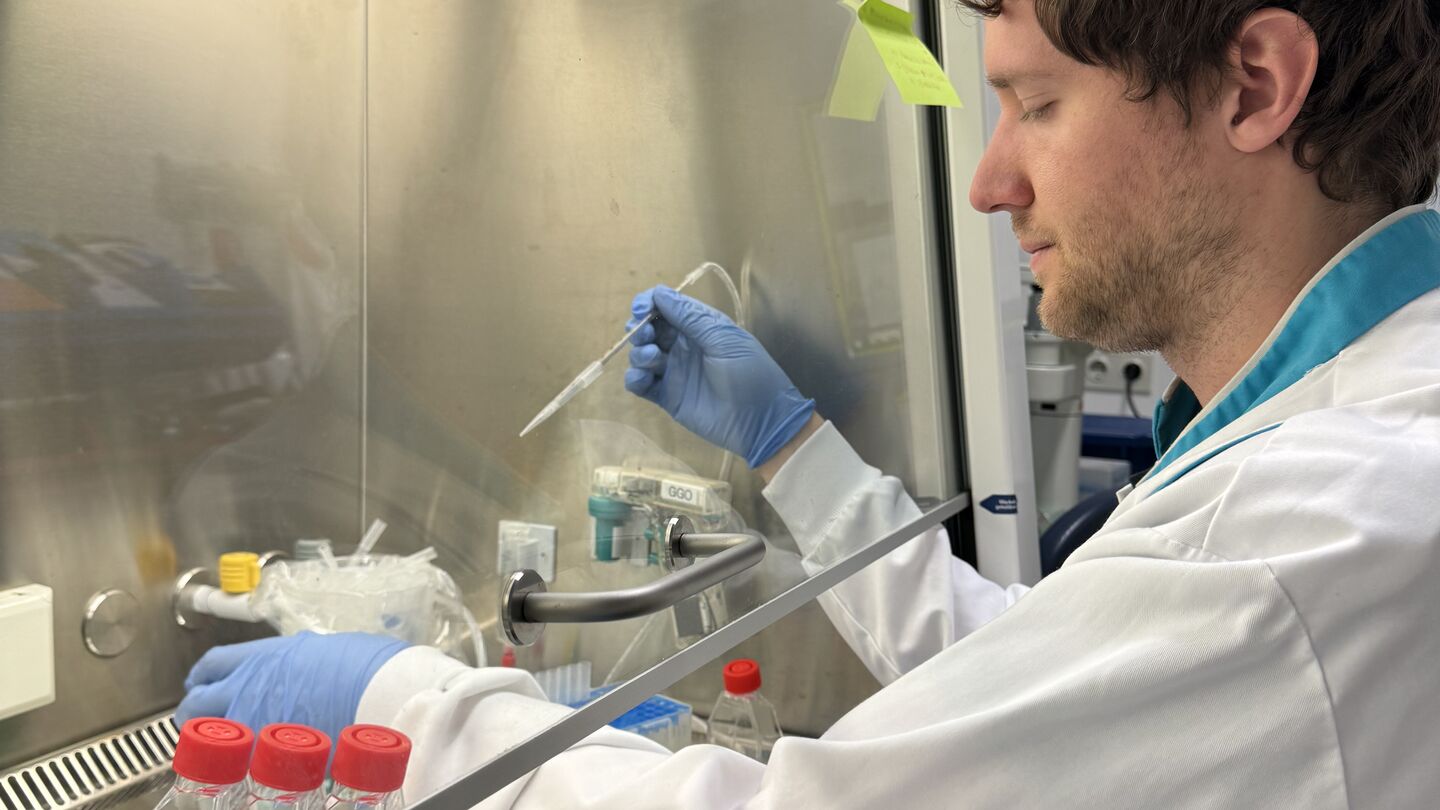

TU/e researcher Robby Zwolsman developed a new, tiny lipid nanoparticle that can efficiently package genetic material and deliver it to the right place in the body. This is an important step toward applying RNA immune therapy. Last Thursday, he defended his PhD research at the Department of Biomedical Engineering.

He compares it to the step-by-step instructions for assembling the world’s most famous bookshelf. Using your own body as a medicine factory requires such a detailed plan, Zwolsman explains. “If you can deliver small pieces of RNA into cells, they can produce therapeutic proteins on-site. The instructions have been greatly optimized recently, but they remain very fragile.” He smiles. “Spill a cup of coffee over your instructions, and the frustrations quickly mount.”

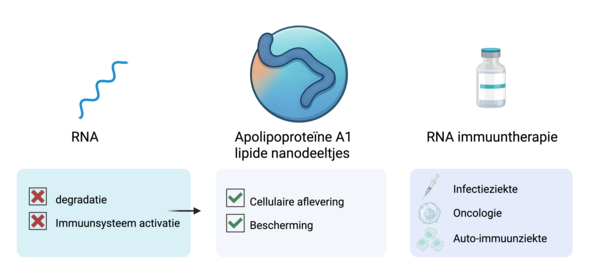

And that is exactly why Zwolsman spent the past few years at the BME Precision Medicine research group working on an entirely new delivery system. By packaging the genetic material—small RNA fragments—into lipid nanoparticles, it can travel more stably through the body. This is already used in clinics, for example in treating hereditary amyloidosis, to deliver RNA fragments to the liver.

Body’s own address label

But the group led by full professor Willem Mulder and associate professor Roy van der Meel takes a unique approach. They are developing an innovative nanoparticle based on a body’s own nanotransport system. These apolipoproteins can bind various molecules—such as hormones, cholesterol, vitamins, and even small RNA fragments—and transport them through the body. As one of Mulder and Van der Meel’s first students, Zwolsman was at the proverbial cradle of this new platform technology.

“The lipid nanoparticles currently used as the ‘gold standard’ mostly end up in the liver. That’s fine for general vaccines or for treating liver diseases, for example. But we want to direct our delivery system to other parts of the body. That’s why we give our packaging a clear address label.”

Zwolsman explains that their focus is on immune cells. “We want to activate these cells to attack cancer cells, or slow them down in cases of autoimmune diseases like type 1 diabetes or Crohn’s disease. By delivering medicine in a targeted way, treatments can be more efficient with fewer side effects.”

Molecular library

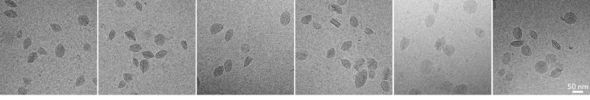

Developing that address label meant long days in the lab for Zwolsman. “We had to start from scratch. There are many variables that influence where a particle ends up in the body—for example, size, shape, charge, and the presence of certain lipids and proteins.” Zwolsman created countless formulations using a molecular library he developed with colleagues. With slightly different recipes each time, he mixed lipids and proteins like a molecular cook, then examined the nanoparticles under an electron microscope after a week.

“We tested many lipid nanoparticles with different properties. Our wish list guided us: the new particle must be able to incorporate nucleic acids, be stable, and release the RNA at the correct location.” He describes it as “a true trial-and-error process” that required “endless patience and, above all, perseverance.”

Rugby ball with potential

Those long lab days have paid off. Using the molecular library, they developed a rugby ball–shaped particle that can deliver RNA more precisely to immune cells. The platform is further optimized with innovative dendrimers. These tree-like structures can enhance the eventual protein production. This appears to be the key, Zwolsman says enthusiastically. “It makes both incorporation and release of RNA much more efficient, but especially delivery to immune cells is very successful. Using fluorescently labeled RNA, we see that these new lipid nanoparticles perform significantly better than the existing delivery method. We have also demonstrated this in in vivo studies in mice.”

The new formulation shows both academic and commercial potential, as evidenced by the two patents that have already resulted from Zwolsman’s work. Therapeutic applications, such as RNA immune therapy for cancer, are now a significant step closer, he emphasizes. “Our lipid nanoparticles can wake up the immune system to attack tumor cells. An aggressive tumor type, myeloma, is normally resistant to immune therapy. But with our nanoparticles, we can induce remission of this tumor in a mouse model; we see no symptoms. After years of mixing molecules, our platform can really make a difference.”

PhD in the picture

What do we see on the cover of your dissertation?

“An artistic interpretation of a special phenomenon observed when mixing components to make our nanoparticles: laminar flow. The fluid layers move, but it looks like they’re standing still. You can also see a wave in it—my great passion is surfing.”

You’re at a birthday party. How do you explain your research in one sentence?

“I make body’s own nanoparticles with special properties that can activate or turn off immune cells. Funny enough, during COVID I was often the ‘vaccine expert’; the COVID-19 shot was the first mRNA vaccine.”

How do you unwind outside your research?

“On the water; I surf as much as possible. On weekends, I’m often in Hoorn, where I grew up. With the IJsselmeer and Markermeer on one side and the North Sea on the other, you can get on the water in any wind direction. It’s a way to clear your head and surrender to the forces of nature.”

What advice would you have liked to receive as a beginning PhD candidate?

“It takes time to achieve something meaningful. Some studies take years. Before your PhD research takes the shape you want, it requires a lot of time. It demands patience and perseverance; don’t give up too quickly.” He chuckles. “It’s something I also learned as a surfer in cold water.”

What is your next chapter?

“I now work at Ethicon, a subsidiary of Johnson & Johnson. They develop a hemostatic patch made of biomaterials. It feels good to be patient-focused; if this material is approved, it goes directly to the surgeons. This way, I can contribute to patient recovery. I didn’t consciously leave academia, but I was looking for more stability. Also, it’s great for my Spanish fiancée, who moved to the Netherlands.”

Discussion